28

Shreds And Patches

Polly didn’t consciously seek medical help in the wake of the upsets of late October and early November. She just took baby Katie Maureen for their regular check-up.

“There; you can get dressed again, now,” said Bruce Smith. Politely he retired beyond the screen.

“You don’t have to do that, you know,” said Polly’s voice, sounding muffled—she must be pulling her blouse over her head.

“Yes, I do—medical ethics and all that jazz. Besides, I might go mad with desire if I watched ya put your clobber back on,” replied Bruce, grinning.

Polly came round the screen laughing, doing up the zip of her slacks. “Isn’t it daft?” she said. “I mean, you’ve just been examining me without my clothes on; you must’ve seen my body...” She paused, lost for words to express the number of times Bruce had seen her body. “Millions of times!” she ended.

“Yeah, daft,” he agreed. “Siddown, Polly.”

“Hang on, I’ll just see if Baby…” replied Polly vaguely. She turned and went over to Katie Maureen, who was fast asleep in her carrycot. She picked the baby up and sat down, cuddling her. Over Katie Maureen’s small gingery head the wide grey-green gaze was defiant. “Well, what’s the verdict?” she said aggressively.

Bruce didn’t fail to note the implications of this behaviour. “You’re one of the healthiest women I’ve ever seen,” he said mildly.

“Oh,” said Polly. She laid her cheek on the baby’s head.

“And Katie Maureen’s one of the healthiest babies.” He’d already told her so.

“She’s so small,” Polly said dubiously. “I know the twins were tiny at first, but...”

“Girls often are,” said Bruce. He grinned. “Give her a chance!” Polly smiled uncertainly. “That reminds me,” he said. “How did the twins’ birthday party go?”

Polly opened her mouth. An expression of false cheer came over her face. She caught Bruce’s eye. She shut her mouth again, the expression of cheer fading. Finally she admitted: “It was ghastly. Mum and Aunty Vi were potty with excitement, of course, and Jake was practically hysterical. He had these awful clowns that came and—uh—clowned—all over the lawn: they had that awful clown make-up on—you know, like they do—and the poor Twinnies were scared out of their wits!”

“Oh, Lor’,” said Bruce.

“I told him they were too little,” said Polly. Her soft contralto began to rise. “I told him over and over, but he wouldn’t listen, and he insisted on the bloody clowns, and a conjurer and masses of cake and jelly and muck, and Davey and Johnny were both sick! I told him their stomachs couldn’t cope with all that sweet stuff, they’re not used to it, but he wouldn’t listen! He’s getting worse, Bruce! And you should’ve seen the stuff he bought for them! Trikes, and God knows what. Johnny fell off his and got an awful bump on his forehead... And he bought them these dreadful plastic guns, Bruce! And then he was showing them how to work them and he shuh-shot old Grey!”

Bruce knew that the cat had been the cause of friction between Polly and Jake almost since they first met. In his opinion Jake was jealous of the bloody animal. Only he hadn’t thought he’d go that far! “Shot him?” he echoed in horror.

“Only with a ping-pong ball,” said Polly in a trembling voice. “But it gave him an awful fright, Bruce: he was on the front lawn, for once, just sunning himself.” Her voice shook. She sniffled. “He hardly ever comes out onto the lawn, these days,” she said. “And then Jake had to go and—”

“Yes,” said Bruce quickly before the awful threat of laughter could overwhelm him. He rubbed his nose. “It’s only the proud father syndrome, Polly.”

“I know, but he didn’t have to— Anyway, I threw the rotten guns off the cliff!” said Polly defiantly, glaring at him.

Oh, Lor’! thought Bruce. “It seems to have been a merry party all round,” he ventured.

Polly gave a sheepish laugh. “Yeah—was,” she agreed. She laid her cheek on the baby’s head and sniffed. Silently Bruce handed her a clean hanky. Polly blew her nose. “We were getting on so well,” she said. “I mean, we’d agreed about me getting on with my writing, and just doing a bit of tutoring for a few years—you know, I told you.”

“Mm,” agreed Bruce.

“And Jake cancelled that trip to Japan; and we decided he won’t go on any more business trips unless I can go with him—well, not unless something urgent comes up; did I tell you that?”

“Mm,” he said again.

“And everything was going swimmingly! Well, except for the sex thing,” she amended.

“Mm... That getting to him, is it?”

Polly frowned. “I don’t know. He understands that—that it’s too soon to start worrying, of course.” She flicked a glance at him which Bruce affected not to notice. “He likes what we do do...” she said slowly. “I dunno; it’s hard to tell with a man, isn’t it?”—Bruce didn’t react in any way to this odd query.—“I don’t think it’s so much the intercourse itself that he’s missing,” she said cautiously. “It’s more that it’s upsetting him that I don’t feel like it. –Blow! I don’t think I put that very well.”

“I think I see what you mean.”

Polly frowned thoughtfully. “Maybe there’s some sort of guilt there,” she said. “You know: he feels it’s partly his fault because I can’t get aroused.”

“Mm,” agreed Bruce.

“Only I don’t think it’s really that, either. Well, not altogether.” She paused. “I think he feels unhappy... Damn! It’s so hard to explain!” She scowled. “He can never feel quite comfortable unless I come, too,” she said. She looked at Bruce without much hope. “I dunno what the psychology of it is, but anyway, that’s how he feels.”

“I dunno what the psychology of it is, either,” said Bruce simply, “but I think I understand.”

“It’s not just guilt, or— I suppose it’s partly his responsibility thing, but… Well, anyway!” She gave a breathless laugh.

“Mm. All that’ll come right, you know,” he said without emphasis.

Polly went red.

“Given time,” he added. She was looking away from him. “But that doesn’t mean I don’t need to know about it.” The wide grey-green eyes switched quickly to his face. Bruce grimaced comically. “Just in case it doesn’t come right,” he said mildly.

“Yeah,” said Polly gratefully.

There was a silence.

“He’ll simmer down, now the excitement of the baby coming and the twins’ birthday is over.”

“I hope so, because if he doesn’t simmer down pretty soon, I think I’ll go bonkers!” She gave an unconvincing laugh.

Bruce rubbed his nose slowly. He hated making suggestions: he liked his mums to come up with their own solutions to their problems, if possible; and of course quite often all they needed to do was talk about it, get it out of their systems...

“You mentioned guilt, back there.”

“Ye-ah...”

“Well, has it occurred to you that maybe he is feeling guilty, only not over the sex thing, so much, but over the job thing—you deciding not to go back to full-time lecturing, and that.”

She goggled at him. “Cripes,” she said faintly.

“Could be,” Bruce said mildly.

“Yes! I’m sure you’re right! Why didn’t I think of that?” she cried.

Why, indeed? thought Bruce.

Polly was thinking it over. Katie Maureen whimpered, and nuzzled her. “Ssh, Baby; ’s not lunchtime yet,” she said in a vague voice. “Yeah, I’m sure you’re right, Bruce. He’s been so, um, hyperactive, really; yes, that must be it!”

Bruce murmured: “Mm.”

“What on earth can I do about it, though?” said Polly, suddenly looking lost.

Bruce fiddled with his ballpoint pen. He opened his jelly-bean jar and took a black one. “We-ell…” he said. “Wanna black one?” he added generously.

“No, I hate the black ones,” said Polly. She looked greedily at the jar. “I like the green ones.”

Bruce passed her the jar. “Take several,” he said.

Polly took several green jelly-beans. She passed the jar back.

Bruce took another black one. “What I reckon,” he said eventually, “is that you could stop blaming him, Polly.”

“Blaming him?” cried Polly indignantly. “What do you mean?” She glared at him.

Bruce looked at her mildly.

She went very red. “Shit!”

“Mm,” said Bruce, pursing his mouth up horribly. He waggled his eyebrows at her.

“Always swore I wouldn’t do that,” said Polly.

“Mm.”

There was a silence. Bruce ate another black jelly-bean, sighed, and screwed the jar up tightly.

“Bugger,” said Polly heavily. “It’s the ‘Everything’s His Fault’ syndrome, isn’t it?”

“Could be,” he agreed.

She frowned. “I chose to marry him; I decided to have kids; I decided not to go back to work full-time.”

“Tell yourself that five times every night and morning,” said Bruce mildly.

“Yes, and what’s more I agreed to build the new house—in fact, I designed the bloody living-room,” she said grimly.

“Mm.”

Polly met his eye. She pulled a rueful face. “I s’pose, if you come right down to it, poor old Jake’s probably not responsible for me turning thirty-two this month, either.”

“No; probably not,” he said dubiously.

Polly gave her little choke of laughter. Bruce grinned. A companionable silence fell.

“Bruce,” she said eventually: “how the Hell can I stop myself?”

Bruce scratched his head. “Keep busy?” he suggested.

“Yeah,” she agreed gloomily.

“Lots of fresh fruit and veges and fresh air,” he added.

“Yes... It’s been so windy lately; I s’pose I have been cooped up indoors a lot... “ She turned scarlet. “I think I’ve been hiding, actually.”

“Hiding? Oh: with all those relations round the place- “

“Not just them,” she said with a sheepish smile. “Though they were a factor, I must admit. Thank God they’ve all gone! No, it wasn’t just them, really, it was more…” She swallowed painfully. “What happened on Labour Day,” she said hoarsely.

“Labour Day?” asked Bruce blankly, thinking he must sound almost as stupid as he felt.

“Yes; Mum and Dad took the twins to the zoo and Jake and I stayed home with Baby.”

“Oh?” said Bruce cautiously, thinking they must’ve had a row.

Polly leaned forward, baby and all. “Bruce, if I tell you, you swear you won’t breathe a word to anyone?”

Bruce Smith didn’t protest at the slur cast on his professional discretion. “Yeah; go on.”

Polly burst out with the story of Sylvie’s scene on their patio. It took a while, as it necessitated imparting certain details of Hamish’s private life that she hadn’t mentioned before. Bruce didn’t reveal that, since he’d attended Hamish for his flu in May, several of these details were already known to him. He didn’t, personally, feel that it had been anything but a storm in a tea-cup: well, an hysterical middle-aged woman; and it certainly didn't sound as if she'd done anything worse than a bit of screaming and swearing—or intended anything worse. Just looking for someone to blame for her life being in a mess. But then, he wasn’t Polly, was he?

“I think,” she admitted shamefacedly at the end of it, “that I’ve been kind of afraid she’d come back—you know.”

“Has the gate been fixed?” asked Bruce practically.

Since Polly’s mind was fully as logical as his own she didn’t make the mistake of assuming that this question was either patronising or meant as a dig at her. “Yes, it’s fine. I know nobody could get in; only…”

Bruce scratched his head again. “Yeah.” He thought of that time three years back, when that mad ex of Jake’s had shot Polly in the arm—on the patio of the old house, come to think of it; no wonder the poor darling had phobias about mad middle-aged ladies attacking her in her own home!

“Crikey, Polly,” he said. “I dunno what to say.” She was looking at him hopefully. “Look,” he said weakly, “if it’s been getting to you that much—” He hesitated. “Look, I know a very good man you could see—have a wee chat with, eh?”

Polly looked at him suspiciously. “Not one of those middle-aged smoothies,” she warned.

“No, he isn’t like—”

“And not one of those young twerps that’ve done a B.A. in psychology and think they know it all; I’m brighter than them!” said Polly loudly.

“No; shut up,” said Bruce.

She goggled at him.

“Don’tcha trust me?” he said.

Polly turned scarlet.

“He’s a good bloke; you’ll like him.”

“Jake’ll have kittens,” she replied.

Recognizing this for assent, Bruce scrawled the name and address of his pet psychiatrist on a prescription pad. “Here. I’ll make an appointment for you.

“Ta.” She looked at the up-market address. “Remuera?”

“Now, now; mustn’t be prejudiced,” said Bruce, grinning broadly.

“Do you think it’ll help?”

“Can but try.”

“Do you think it’ll make me feel braver?” said Polly. Her voice trembled.

“Well, the best thing’d be to put this Sylvie woman in a potato sack with a great hunk of concrete and drop her off the Harbour Bridge. But failing that—”

Polly chuckled weakly. “Yes. Well, I’ll give it a go.” She paused. “Do you think I could talk to him about Jake, too?” she said, going pink.

“Yes, I think that’d be a good idea,” said Bruce, just as if it hadn’t occurred to him some time back.

“Bruce—” said Polly.

“Mm?”

“Ta.”

Bruce just grinned.

“The cupboard looks really nice, doesn’t it?” said Mirry for about the five-hundredth time since they’d installed it after Labour Weekend.

“Aye,” Hamish agreed, for about the five-hundredth time.

Mirry looked round at him cautiously. He was glaring into the open dishwashing machine. She looked back into the dining-room, where the Fields’ nice old kauri corner cupboard was now the sole item of furniture. “We’ll have to get a dining suite to match it,” she said in a squeaky voice.

Hamish sighed heavily. Mirry flushed, and continued to stare into the dining-room.

“One like Aunty Polly’s ’ud be nice,” put in Elspeth brightly.

Hamish and Mirry both jumped.

Mirry turned round and looked gratefully at Elspeth. Elspeth was sitting on the edge of the kitchen table swinging her legs, and eating the last of the apple crumble out of the baking dish.

“Yes,” she agreed, “only theirs is mahogany, I think.” She looked at Hamish out of the corner of her eye. “We’d have to get kauri... or something that’d go with it.”

Hamish didn’t react.

“That was a nice table we saw at Forrest Furnishings today,” Elspeth reminded her. “You said you liked it, Mirry.”

Mirry went scarlet. “Yes,” she said in a strangled voice, not daring to look at Hamish.

He looked up from the dishwashing machine. “Will this plastic mug of Elspeth’s go in the dishwasher?”

“No, I think it’d probably melt,” said Mirry, not meeting his eye.

Hamish looked at the mug, which had an evil-looking cat on it. “Good; then I think I’ll put it in.”

“Da-ad!” protested Elspeth. She got up and took the mug off him. “That’s my Golf Club mug,” she said. She marched over to the bench with it.

“Golf Club?” repeated Hamish vaguely.

“Da-ad!” cried Elspeth. “You know: the one I won! For collecting the most lost balls!”

“That day she went up there with Jill and Gretchen,” Mirry reminded him.

“Oh, aye,” he remembered.

“Honestly, Dad! You’re hopeless!” Elspeth informed him.

“What’s all this about you and Mirry going to Forrest’s?”

“What? Aw,” said Elspeth. “After school…” She put a lot of detergent into her cat mug.

“Don’t use so much detergent, it doesn’t grow on trees,” he said.

Weakly Mirry explained: “We had afternoon tea at The Primrose Café, and it was raining; so we just wandered down the Arcade and went into Forrest’s—for a look.” Her voice shook.

“Oh, aye?” said Hamish. “Was it a nice afternoon tea?” he asked Elspeth.

Elspeth had run hot water into her mug and made a huge mound of bubbles. “Yeah; good-oh,” she said. She blew experimentally at the bubbles. “I had two cream doughnuts.”

“Ugh!” said Hamish involuntarily.

“They were nice,” she protested in an injured voice.

“I hope you didn’t have cream doughnuts,” he said to Mirry.

“She thinks they’re gross; she only had cappuccino,” said Elspeth before Mirry could reply. She blew a lot of froth off her mug.

“Yes,” agreed Mirry limply.

“‘She’ is the cat’s mother,” said Hamish firmly to Elspeth.

“Mirry, then,” said Elspeth. Cautiously she ran more hot water into her mug.

“Stop wasting hot water,” he said. He smiled at Mirry. “I’m glad you restrained yourself in the matter of cream doughnuts. I’d hate you to get fat.”

“She won’t get fat!” said Elspeth scornfully.

“Anyway, I don’t like them,” said Mirry.

He went over to her and put his arm round her. “Good,” he said. “What’s all this about dining tables?” He smiled at her.

In spite of the months they’d had together Mirry still got all trembly inside when he smiled at her. She not infrequently got all tongue-tied, too. Added to which, what with his odd, moody behaviour lately, she was far from convinced that he wanted her to run round Puriri spending large sums of his money on pieces of furniture which he seemed quite content to do without. In fact she was far from convinced that he wanted her in the house permanently, let alone items of expensive furniture of her choosing. For all of these reasons she went very red. “We were just looking,” she croaked.

Elspeth ran the hot water again.

“Stop wasting that water!” said Hamish loudly without looking at her.

Elspeth pouted. She put her mug upside-down on the bench and watched with interest as a lot of bubbles formed round it.

Hamish gave Mirry a squeeze. “Was it a nice table that you saw, darling? Or was that only her opinion?”

Elspeth snorted. She poked her mug with a cautious finger. It slid along the bench towards the sink. Hastily she caught it and put it back on its pile of bubbles.

“Well, it was quite nice,” said Mirry. “Only it was a bit modern, I thought.”

“Mm; perhaps we should look in the antique shops for a nice old table?”

“Yes,” said Mirry, “only Veronica says—” She stopped.

“Mm-m?” murmured Hamish vaguely. He squeezed her again.

“Well, she says you have to know what you’re buying; you get a lot of done-up junk: you know, tables with legs that don’t belong to them... That sort of thing.”

“Oh,” he said vaguely. “Well, that wouldn’t matter, really, would it? I mean, so long as it looked all right.”

“Yes; but Veronica says you end up paying far too much, if you don’t know what you’re doing,” said Mirry, going very red.

“Oh, I see. –Would you like coffee, sweetheart?”

“Yes, please,” said Mirry, giving up.

“Give me a kiss, first,” said Hamish, smiling down into her eyes.

“Yuck!” said Elspeth loudly by the bench.

Hamish put his hands on Mirry’s shoulders. “Haven’t you got any homework to do?” he said to Elspeth. He wrinkled his nose at Mirry. She trembled a little.

“No; I did it all yesterday!” retorted Elspeth triumphantly. She picked up her mug and held it upside-down over the sink. A blob of suds fell out. She shook the mug but no more suds came out.

“Well, in that case,” said Hamish mildly, “you’ll have to stay here and suffer, won’t you?” He stooped and touched Mirry’s lips with his. “Ma wee pet,” he said softly.

“Ugh, YUCK!” said Elspeth.

They ignored her. Hamish swept Mirry into a tight embrace. Her arms went round him.

Elspeth looked inside her mug. “Sickening,” she mumbled. Her ears went very red. She picked up a tea-towel and began to dry her mug. When she thought they’d finished she said: “Forrest Furnishings is in the Arcade. You know, you go right down it and it’s at the back.”

They didn’t react.

“Where you walk through to Seddon Street!” said Elspeth loudly.

Hamish smiled into Mirry’s eyes. She smiled back. “We could go down to Forrest’s on Saturday morning, if you like,” he said.

“They’ve got some nice rugs,” returned Mirry idiotically.

He kissed her ear. “Aye, we can look at the rugs.”

Elspeth said eagerly: “Can we buy a rug for my room?”

“You’ve got carpet,” he said, releasing Mirry reluctantly.

“Aw-uh, I wanna rug!” whinged Elspeth.

“Well, you won’t get one if you ask for it like that,” said Mirry mildly.

Elspeth went very red. “There was that one with the sweet wee puppy on it,” she muttered.

“It sounds sickening,” said Hamish. He strode over to the bench and picked up the coffee-pot. “Strong, very strong, or hot and strong?” he said to Mirry.

She replied in a strangled voice: “Just strong.”

“Aye, well—I suppose we could always have it hot and strong later.”

“Hamish!” said Mirry, on a strangled choke of laughter.

Elspeth hadn’t understood any of this; she ignored it. “It really was a nice rug, Daddy; and it wasn’t all that dear; and Mirry said you might let me have it.”

“I did not!” said Mirry indignantly. “All I said was you’d better ask him!”

“Aye, well, if that was all you said I’m definitely saying ‘no’,” said Hamish grimly. “I don’t appreciate half-truths.” He filled the bottom half of the coffee-pot with water.

Elspeth went puce. “I’m sorry, Daddy,” she mumbled.

“Aye, so I should bluidy well think!” he said. He put the ground coffee in its compartment.

Sadly Elspeth reported: “It was an awfully pretty wee rug; the puppy had a red bow round his neck.”

“Definitely sickening,” said Hamish, trying not to laugh.

“Where is Puppy?” asked Mirry vaguely.

“On your bed, I think,” said Elspeth.

“What? Oh, no, my new coat’s on that bed!” She rushed out. They heard her clatter across the dining-room and the family-room. She pounded up the stairs.

“I bet he’s lying on it, the wee sod,” said Elspeth gloomily.

Trying very hard not to laugh, Hamish replied: “Don’t say ‘wee sod’; anyway, it’ll teach her to hang her coat up, won’t it?”

Elspeth met his eye. She snickered. Hamish chuckled.

“Lovey, run and tell her not to come down,” he said. “I’ll bring the coffee up.”

“Righto,” said Elspeth obligingly. She thudded out through the dining-room and family-room to the foot of the stairs.

“MIRRY!” she bellowed.

“What? –Get off that coat, you horrible animal!”

“Dad says, don’t come DOWN, he’ll bring the coffee UP!”

“Okay!” cried Mirry.

Suddenly Puppy rushed downstairs with his tail between his legs. He pushed his wet nose into Elspeth’s hand.

“You’re not a horrible animal!” said Elspeth loudly. “You’re much prettier than that old coat!” She led Puppy into the kitchen. “Dad,” she said, “ya haven’t finished loading the dishwasher, ya dill.”

“What?” said Hamish, swinging round.

“Uncle Harry says—” she began.

“Yes, well, don’t you say it. –Not to grown-ups, anyway,” he added fairly.

Elspeth went and got the dishwashing powder. She measured it carefully. She put it in the machine. “Do you want that pudding dish in here?”

“What? Oh—I don’t know.” He picked it up. It was Pyrex. “Aye, well, I suppose it can’t hurt,” he said doubtfully. “Mebbe I should give it a wee rinse, first.” He looked at it again. “You’ve licked it pretty clean,” he said weakly. “Here.” He brought it over and put it in the machine.

“Not like that!” said Elspeth scornfully. She rearranged it and closed the machine.

“Well, go on,” said Hamish.

Beaming, Elspeth set the controls and switched the dishwasher on. “Forrest Furnishings is down The Arcade,” she said again.

“Aye, I know.” Gingerly he opened the lid of the coffee-pot. Nothing had happened. He frowned, and closed it.

“The Cheese Basil’s in the Arcade,” said Elspeth in the local vernacular.

“Aye.”

“Upstairs.”

“Mm.”

Elspeth took a deep breath. “Mirry said mebbe one night, if I was very good, mebbe you’d take us there for dinner.” She paused. “I have been quite good,” she said dubiously.

He gave her a hard look. “Is that exactly what she said?”

Elspeth looked as if she was about to explode. She nodded frantically. “Yes, exactly. Exactly, Daddy! I’m not telling one of those... what you said. Honest, Daddy!”

“Aye, well. Mebbe I might, at that.” He paused. “When Mirry gets her exam results,” he said. “It’ll be a—a kind of family celebration, okay?”

Elspeth embraced him ecstatically. She hurtled out of the room. Her footsteps pounded across the dining-room. “MIRRY!” she bellowed. Hamish shuddered. Elspeth’s footsteps pounded across the deserted family-room. Hamish shuddered again. “Aye, the sooner we get some rugs into this place, the better,” he mumbled.

“MIRRY!” bellowed Elspeth from the front hall. “Dad says he’ll take us to the Cheese Basil!”

Hamish could hear her pounding up the stairs. “MIRRY!” she was bellowing again.

“Aye, and the next thing, I suppose she’ll be demanding a new dress for the occasion,” he said crossly to the coffee-pot. His long mouth quivered into a smile. “I suppose they both will,” he said. His eyes went wide and dreamy.

After a while it dawned on him that the coffee-pot still hadn’t done anything. He could hear the television from upstairs; he hoped to God it wasn’t Coronation Street, to which Mirry and Elspeth had both become addicted over the past few months. His eyes came back into focus and he saw that he hadn’t turned the heat on under the pot.

“Och, bugger it!” he muttered. He turned the element on and sat down weakly on a kitchen chair. Puppy came and sat beside the chair, looking up at him with soulful eyes.

“And what the bluidy Hell do you imagine you’re getting?” he said nastily.

Puppy went on looking at him.

Hamish sighed. He ran his hand through his curls. The gloom that had possessed him earlier as he drooped over the dishwasher re-invaded him. They should have their M.A. papers back from Wellington by the end of next week and Mirry would get her results; then he’d have to tell her... He decided that they’d have the jaunt to the Chez Basil first, and then he’d tell her. He felt terrible.

Puppy pushed his wet nose into his hand.

Hamish jumped.

Puppy licked his hand.

“Och, go on, then,” he said weakly. He got up and got the packet of Mallowpuffs down from the top cupboard. “Just one,” he said in a threatening voice. He put one down on the floor. Puppy quivered all over. “Go on, boy,” he said.

Puppy engulfed the Mallowpuff. His tail wagged madly.

Hamish looked at the packet again. “Not on top of cream doughnuts,” he said. He put it back in the top cupboard.

He sat down and stared blankly at the stove. They’d go to Forrest’s on Saturday, anyway: she’d like that. And perhaps do a tour of the antique shops—Veronica would know where they all were, he must give her a ring. Perhaps they’d find a rug for the dining-room at Forrest’s...

“Dad!” said Elspeth’s voice sharply.

Hamish jumped violently.

“Mirry says, are you growing those coffee beans, or what?” She went over to the stove. “This coffee’s done!” she discovered accusingly.

“I was wool-gathering,” he said lamely.

Elspeth sniffed. “So I gathered.”

Hamish winced. She sounded just like Mirry’s mother.

Having finally made up her mind to it, Sylvie paid over the vast sum demanded by the Hinemoa Street Service Station for having kept her little car dry and sheltered for almost a year. He should have paid, of course: it had been his idea in the first place,

“She’s all ready to go,” said Greg Anderson in an encouraging voice, either not noticing or ignoring Sylvie’s tight-lipped anger. “Full tank.” He patted the car’s bonnet encouragingly.

Sylvie immediately looked to see if his unsavoury, black-nailed hand had left a greasy mark; unfortunately it hadn’t, so she couldn’t jump on him for that.

“I hope you’re not charging me extra for that,” she said sourly.

Greg wasn’t charging her extra, he was charging her the ordinary price for a full tank of petrol. He replied cheerfully: “All part of the service!”

Sylvie snorted. “I’ll have a receipt for that,” she reminded him.

“Uh—yeah; hang on a mo’,” said Mr Anderson weakly. He retreated into the fastness of the service station’s glossy glassed-in spare parts and necessaries area and said weakly to Adrienne on the till: “Ring this up for us; she wants a receipt.”

Used to the vagaries of customers, Adrienne did this without comment.

Sylvie took the receipt and got into the car without comment.

Margaret Prior, who’d come with her, got in beside her, wondering if she should say something; as she was aware of Sylvie’s fury over Hamish’s refusal to pay for the car’s storage it was hard to think of anything that was tactful enough. Finally she offered weakly: “It’ll be nice to be mobile again, won’t it? It’s such a nuisance, having to rely on buses and taxis.”

“Aye,” said Sylvie grimly.

When they got to Kowhai Bay Road she parked the little car at the bottom of the steep concrete drive leading to the house that had once been hers and by rights still should be, and said grudgingly: “You don’t have to come up; I’ll just collect my clubs.”

“I don’t mind,” returned Margaret mildly, getting out of the car. She was quietly determined to prevent an acrimonious confrontation between Sylvie and Hamish—or, worse, Sylvie and poor little Mirry.

As it turned out she didn’t need to play the rôle of peacemaker after all, because Hamish, after speaking to his stony-voiced wife on the phone the previous evening, had chickened out on an actual meeting and had left her golf clubs on the front steps. Sylvie was very keyed up at the thought of having to meet him face-to-face and the wind was thoroughly taken out of her sails when she found she wouldn’t have to, after all.

“Well!” she said at last. “Typical! I suppose it never occurred to him that anyone could just walk up here and steal my clubs!”

Margaret murmured vaguely that they didn’t have much crime in the Bay. Sylvie snorted, snatched up the bag, and began to march down the drive. Margaret looked about her at what Mirry had managed to do with the small pieces of terraced earth left here and there between the Beckinsales’ vast expanses of concrete and said: “Isn’t the garden looking nice?”

Sylvie snorted again.

Margaret lapsed into silence. Still, at least it was a good sign that Sylvie was taking up her golf again. She began to wonder if she should introduce the topic of Elspeth today; they had had one meeting (instigated and supervised by Margaret), which neither party had appeared to enjoy, and now Elspeth was making difficulties about a second meeting—well, of course she was only a little girl, she must feel that Sylvie had deserted her—but Sylvie was quite wrong in saying that Hamish was egging Elspeth on, she knew for a fact that he was doing his best to make her see reason. She sighed, and stared absently at an azalea that looked a bit droopy and sick. That position was far too dry and exposed; she must remember to tell Mirry that azaleas didn’t like a hot, windy spot—tactfully, of course: it would never do for dear Mirry to feel she was interfering; and of course she’d never say anything to her about more—well, more personal things, like little Elspeth’s clothes; only she did sometimes think…

“Are you coming, or are you going to admire that weed for the rest of the morning?” said Sylvie drily.

Margaret jumped; her thin, sallow cheeks pinkened. “It’s an azalea,” she said, following her down the drive.

“Nae doot,” replied Sylvie, very Scottish.

On the links Margaret couldn’t refrain from saying: “Your swing has improved!”

Sylvie stopped staring down the fairway after her ball with narrowed eyes, flared nostrils and grimly triumphant mouth, and replied with satisfaction: “Aye, it has that; I had some proper coaching in Edinburgh!”

Margaret didn’t know whether that remark was a good or a bad sign; as a result she sent her own ball fair and square into a large tree.

They searched for it for some time.

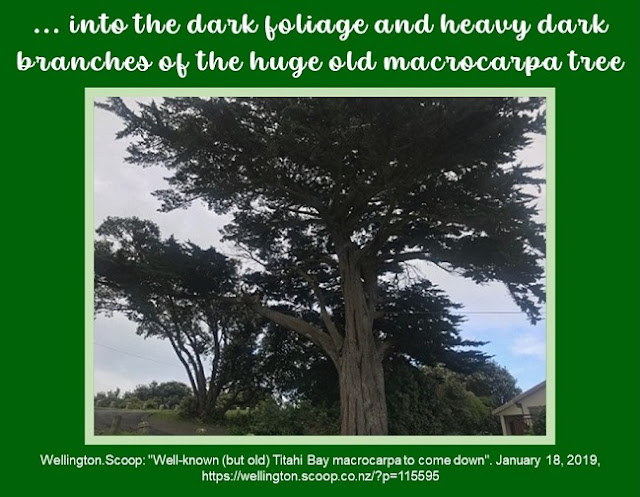

“I think it must be in the tree,” said Margaret at last, looking sadly up into the dark foliage and heavy dark branches of the huge old macrocarpa tree.

“Aye; lost ball, then?”

“Mm,” she agreed unhappily.

It wasn’t supposed to be anything more than a friendly practice round; nevertheless Sylvie kept score and announced her own resounding victory with grim satisfaction.

“My game has improved,” she conceded.

“Yes; it’s a pity the hot weather’s coming up; never mind, there’s the Carrano Cup before Christmas, you could put your name—”

“The what?” demanded Sylvie hoarsely.

Margaret was so used to the phrase “the Carrano Cup” (for which the Puriri Golf Club ladies had been playing for the last ten years) that she nearly said it again. She gulped.

“I will not play for anything with That Man’s name on it! Did I tell you what he said to me—?” She began to tell Margaret all over again what Jake had said to her on Labour Day—or, more accurately, what she’d now persuaded herself he’d said. Polly had poured the whole story into Margaret’s sympathetic and horrified ear on the Tuesday, so she knew who was responsible for that scene, too. She tried to listen without impatience, deciding sadly that, much as she would like to patch things up between Sylvie and dear little Elspeth, perhaps today was not the day, after all.

She made a firm date for another game before they parted; Sylvie accepted eagerly, though silently telling herself, with considerable aggression, that she’d see if she felt like it, when the day arrived.

When the day arrived she went: it was somehow impossible to turn down Margaret’s invitations—unless they were for the declared purpose of talking things over with “dear Hamish”, a mistake that Margaret didn’t repeat.

Gradually she began to feel, as the weather warmed, if not less bitter towards Hamish, then more resigned to the situation. She didn’t admit this to herself; but she didn’t write any more letters.

“Sit down, Carol,” said Miss Fothergill. Instead of indicating the chair that stood before her big desk, she led the way over to the easy chairs and coffee table in the bay window.

Carol Rosen followed her uneasily and sat down in an easy chair. There were some little cakes on a pretty plate on the coffee table. In spite of her unease Carol was young enough to look at these little cakes hungrily.

“Would you like a coffee?” said Old Featherbrain.

Carol began to wonder what the Hell was up. “No, thank you.”

The headmistress of St. Ursula’s said: “I hope you don’t mind if I do,” and poured herself a coffee. She put a lump of sugar into it with a pair of those stupid tongs like Grandma had and stirred it with a tiny spoon. Grudgingly Carol recognized that it was a pretty little spoon.

Miss Fothergill eyed her thoughtfully. She sipped her coffee cautiously, still saying nothing.

Carol went very red and said abruptly: “There’s nothing wrong, is there?”

Miss Fothergill replied kindly: “Nothing wrong at home, no, if that’s what you mean. I just want a chat with you. –Are you sure you won’t have a cup?”

“All right, then; thank you,” said Carol in a growly voice that failed to conceal her immense relief. She looked sideways at her headmistress’s cup of very black coffee and admitted: “With milk, please.”

“Sugar?” said Old Featherbrain, holding the bloody tongs poised over the cubes.

“Yes, please: two,” admitted Carol.

Her headmistress handed her the sugared, milky cup of coffee.

Carol stirred it. Silence fell. Miss Fothergill sipped coffee again and looked at her.

Carol felt like a beetle or something. Desperately she said: “Those are pretty spoons.”

“Yes; they belonged to my grandmother.”

“Oh,” said Carol. She took a gulp of her coffee. It was far too strong.

“Would you like a cake?”

“Thanks,” said Carol weakly, taking a butterfly cake. The headmistress passed her a plate to put it on. “Thanks,” she said again.

“Have a serviette.” She passed Carol a paper serviette.

“Thanks,” mumbled Carol. Desperately she bit into the cake. Cream oozed round her mouth. She put the cake down, tried to lick the cream off her face unobtrusively, and wiped her mouth with the serviette. Old Featherbrain, she saw gloomily, had had too much sense to choose a cream cake. She’d taken a little one with pink icing and was eating it neatly.

When Carol had eaten her cake Miss Fothergill passed her the plate again, and said as she took a piece of ginger slice: “I was quite pleased with your exam results, Carol.”

Her mouth full of ginger slice, Carol goggled at her uncertainly.

Miss Fothergill continued placidly: “You did better than I expected you to; although not as well as you could have, of course. Still, you should have no trouble getting into university next year, though it’s a great pity that you didn’t pull yourself together in time to do enough work to get yourself a scholarship.”

Carol stared. “I don’t need a scholarship,” she said through her ginger slice. She swallowed. “My family can afford to send me to university—if I want to go,” she said aggressively.

Miss Fothergill replied: “Can they?” She gave her a hard look.

Carol went very red. “What do you mean?” she said. Her voice was high and defiant: Miss Fothergill could hear the fear in it.

“I don’t know if you’re aware of it, Carol,” she said, “but it’s your Uncle Nat who’s been paying your school fees this last year.”

“So what?” said Carol sulkily. Miss Fothergill didn’t reply. “He’s my parents’ executor or something, isn’t he?”

Miss Fothergill sighed. “Carol, the cheques were drawn on your uncle’s personal account.” Carol stared at her resentfully. “I gather,” she went on carefully, “that your father’s business had a lot of debts—not that he wouldn’t have cleared them, in time.”

Carol looked at her blankly.

“The point is, my dear,” she said, leaning forward, “that after all the debts were paid there was very little left in your parents’ estate; certainly nothing like enough to pay your fees here.”

Carol’s mouth sagged open. “What about the house?” she said at last. “Didn’t Dad’s insurance pay off the mortgage, or something?”

“Mm, the first mortgage. But they’d recently taken out another mortgage—something to with expanding the business, I believe.”

“You mean there’s nothing?” said Carol numbly.

“Virtually nothing, no. Your uncles have managed to salvage a little; when the estate is finally wound up there’ll be about a thousand dollars each for you and your brother and your little sister, Mr Weintraub says.”

Carol was very white. The scattering of freckles across her elegant nose and high cheekbones stood out strongly. After a moment she said: “What about my trust?”

Miss Fothergill looked at her not unkindly but rather as if she ought to have known better than to ask that question. After a moment she said, rather drily: “All the trusts Sir Jerry Cohen has set up for his grandchildren are in the same terms, I believe.”

“You mean I don’t get any money until I’m twenty-five, because I’m a girl!” said Carol loudly and bitterly. “And if I’m stupid enough to go and get married before then, it all goes to my children!”

“So I understand,” replied Miss Fothergill neutrally.

“It’s not fair!” she cried, going very red. “Rotten Damian gets his when he’s eighteen!”

“Mm.”

Carol’s lips trembled. “He’s a—he’s a horrible old dinosaur!” she burst out.

Miss Fothergill looked very dry, and after a moment Carol admitted: “That sounds stupid; but you know what I mean: he’s still living in the Dark Ages!”

“I quite agree,” said Miss Fothergill briskly, “but there’s no point in going on about it, is there?” She hesitated. “But apart from the trust money, if you asked Sir Jerry, I’m sure he’d—”

“NO!” cried Carol loudly.

There was a short silence.

“I’ll have to get a job,” she said.

“That is a possibility.”

There was quite a long silence. Carol’s bright flush faded. She was very pale again.

“If you do want to go to university,” said Miss Fothergill calmly at last, “I’m quite sure that either your Uncle Nat or your grandfather would be willing to see you through; but I do think you should take stock of your position.” She paused. “You owe it to yourself to take stock of your position, Carol.”

“Yes,” said Carol numbly. She stared at the older woman. “I’ve always just taken it for granted,” she said. “I mean, there’s always been money in the family... I never thought!”

“No,” agreed her headmistress tranquilly. “Your Uncle Nat didn’t want me to tell you; but I thought you had a right to know.”

“Yes,” said Carol. There was a silence. “Thank you,” she said.

There was another silence. Miss Fothergill quietly poured herself another cup of coffee. Carol stared blindly out of the window at the school’s shrubbery and a slice of the front drive.

“I should have asked,” she said at last. “Uncle Micky said I could see all the papers if I wanted to, only I— I mean, I won’t be eighteen until next June, and I just didn’t...”

“Well, now you know,” said her headmistress simply.

“Yes. Thank you,” said Carol again. “I’ll have to think about it,” she added with difficulty.

“Mm.” Miss Fothergill saw that the girl was frowning out into the garden again. She sat quietly, not speaking.

Finally Carol gave a strange laugh. “I thought you said there was nothing the matter!”

Miss Fothergill gave her a steady look. “Well, is there?”

She laughed again. “Most people would think so!”

Miss Fothergill didn’t reply.

Carol sighed. “Just as well old Rose bought it,” she said suddenly.

This was the first time in the past year, Miss Fothergill was certain, that Carol had mentioned her dead sister. “Why?” she replied mildly.

Carol gave another strange laugh. “She was always hopeless with money: always overspent her pocket money; always in debt to me or Damian or borrowing on next week’s pocket money from Mum; she’d never have managed on a shoestring... Oh, Hell!” she said, and burst into noisy sobs.

A huge wave of relief swamped Miss Fothergill. She got up on legs that felt quite weak, and fetched the box of tissues from her desk. Coming back to the bay window, she put the box on the coffee table in front of Carol. She gripped the girl’s shoulder hard for a moment. Then she went out, quietly closing the door after her.

In the outer office the School Secretary looked up quickly from her typewriter. She had been Miss Fothergill’s secretary for nearly fifteen years, ever since Phoebe Fothergill, amidst a storm of controversy, had been appointed at what several members of the Board of Governors considered far too young an age to put the School back on its feet after its old headmistress, whose reign had gone on far too long, had let it run down disastrously both scholastically and physically.

“How’d it go, Phoebe?” she asked.

“All right, I think,” replied Phoebe cautiously. “She’s crying.”

“Oh, good!” said the Secretary, very pleased.

“Ye-es. I think it’s what she needed. She mentioned Rosemary, too.”

“Oh, good!”

“Yes,” agreed Miss Fothergill, sighing. “Poor damned kid.”

The secretary looked at her watch. “Don’t forget you’ve got that lunch meeting today with Sir John Westby.”

“What? Hell! –Thanks, Louise, I had forgotten.”

Louise Churton grinned complacently. “Bet he’ll bend your ear about his latest gyny triumph.”

“God! Don’t!” groaned Miss Fothergill. She threw herself down on the couch that was more normally occupied by nervous bottoms waiting to be summoned to the presence. “I’d kill for a cigarette!”

“Bad example to the gels,” said Louise smugly. “Besides, haven’t you given up?’

Phoebe glared at her. “Why on earth did we have to get landed with a ruddy gynaecologist as Chairman of the Board?” she grumbled. “What’s his interest in the School, anyway? All his kids are grown up.”

Louise choked. “Drumming up business?” she suggested. She gave Phoebe a meaning look. “In more ways than one!” She giggled helplessly.

“Shut up!” gasped Phoebe, collapsing into smothered laughter. “No—ssh, Louise!”

Louise pulled herself together first. She looked at her purple, shaking boss in a superior manner and inserted a fresh sheet of paper into her typewriter. “Take a letter, Mrs Churton,” she told herself.

Phoebe looked at her warily.

“Dear Sir John,” said Louise, typing briskly: “Thank you for your generous offer, but I am sorry to tell you your personal services will not be required this week—”

“Shut up!” hissed Phoebe, tears oozing out of her eyes.

Louise chuckled complacently.

Phoebe blew her nose. “He’s not that bad,” she said weakly. “Just smarmy.”

Louise snorted.

“Complete M.C.P., of course.”

“You can say that again; did I tell you what he said to me, last time he—”

There was a timid tap on her door.

Phoebe blew her nose again hurriedly and sat up straight on the couch, patting at her hair and clothes.

Louise gave her a wink. “Come in!” she called.

A very pink Third Former poked her head cautiously round the door. “Excuse me, Mrs Churt— Ooh! Miss Fothergill!” she gasped.

“Come in, Gillian,” said Phoebe in her best Miss Fothergill voice.

Gillian came in and stood on one leg, hooking the other foot round her ankle.

“Stand up straight, dear; did you have a message for Mrs Churton?”

“Yes—no—for you, really!” gasped Gillian.

“Mm?” She smiled at her.

“There’s a man to see you!” gasped Gillian.

“A gentleman,” said Miss Fothergill mildly. “Thank you, Gillian.”

“Not a gentleman, just a man!” said a loud, genial voice, and Nat Weintraub strolled in, with his hands in the trouser pockets of a very nice pinstriped navy business suit, doing his best to ruin its cut. He winked at Gillian, who turned puce.

“Thank you, Gillian,” said Miss Fothergill again.

Gillian gasped, said: “Oh! Yes!” and shot out.

Nat winked at Miss Fothergill. “Funny little beggars at that age, aren’t they?” he said. He held out his hand, beaming.

Louise Churton observed with great interest and considerable astonishment that Phoebe turned pink as she shook it.

“How are you, Mr Weintraub?” she said; to Louise’s ear she sounded really off-balance.

“Good!” replied Nat, beaming again. “How’s yourself? And how are you, Mrs Churton?”

The two women assured him that they were fine. Nat beamed at them both. Mrs Churton was a bit of a hen, of course—must be fifty if she was a day, too—but quite a nice, fluffy little woman. And Phoebe Fothergill was a fine figure of a woman. He looked at her with frank approval; the severe lines of her heavy fawn linen suit did not hide from his expert eye the fact that she had a damned fine pair of thighs on her, and a bust that was just the sort of bust he liked: something you could really get your hands round. He experienced a strong urge to get his hands round it as he looked at the cream silk blouse: one of those crossover jobs that didn’t have any buttons but tied at the waist—sometimes if they bent over a bit when they were wearing one of those...

“You speak to her?” he said.

Miss Fothergill invited him to sit down on the couch. She sat down beside him and told him all about her chat with Carol and the result of it. “Perhaps we should give her a few more minutes,” she ended, looking at her watch.

“Yeah, can’t hurt,” agreed Nat.

Phoebe was aware that he wasn’t giving her the sort of look a Parent ought to give a Headmistress. She had dealt with all the imaginable varieties of Parent in her time and was more than capable of dealing with Nat; but she was very disconcerted to find that her principal emotion was a strong desire that Louise would push off to lunch. Feebly she said: “Don’t hang on here in your lunch-hour, Louise; I’ll hold the fort.”

“Okay,” said Louise happily. She looked at her watch. “Goodness, is that the time? No wonder I’m starving!” She laughed, and got up. “Now don’t forget that lunch appointment with Sir John, Phoebe!”

“No,” agreed Phoebe gloomily.

When the secretary had pushed off Nat asked: “That Sir John Westby, the one that’s Chairman of the Board, that you’re having lunch with?

“Yes,” said Phoebe gloomily.

Nat chuckled richly. “Whassa matter? Can’tcha stand ’im?”

“No,” admitted Phoebe unwarily.

Nat chuckled again.

“Jesus, I shouldn’t have said that!” she gasped, turning scarlet and sitting bolt upright.

“Why not? ’S only me, and I won’t tell anyone. Besides, I can’t stand him, either!” He twinkled at her, and casually slid his arm along the back of the couch.

“Can’t you?” said Phoebe weakly. She repressed an urge to lean back.

“Nah—smarmy type, isn’t he?”

“That’s just what I was saying to Louise!” cried Phoebe, caught unawares. Her hazel eyes opened wide; she looked right into his face, lips parted a little.

Nat could have taken her then and there. He stared into the hazel eyes, blood surging, and said in a low voice: “Great minds think alike, eh?” He licked his lips.

“Yes,” said Phoebe dazedly, unable to look away. She was sharply aware of his smell, which was a compound of good cigars, good aftershave, and big warm man on a warm day. Being neither a fool nor a virgin she was also sharply aware both of her own desire for him, and the fact that she mustn’t: he was a Parent, and they were forbidden territory. Anyway, he wasn’t her type: too coarse, florid—loud! But in the secret depths of her being she knew that he was her type: he was the type that she’d always—

“He’s got an eye for the main chance, too,” said Nat.

“What? Oh, John Westby! Yes, he never misses a chance to push his barrow.” Too late, she realized she shouldn’t have said that, either. She looked quickly away.

Nat shook with chuckles. “S’pose you’re used to dealing with that type?” he ventured. He looked at her strong profile with enjoyment. Bet that mouth’s done a thing or two in its time, he thought. A tiny shudder shook him.

“Oh—yes,” agreed Phoebe unenthusiastically.

“Tries it on, does ’e?”

She jumped:

“Thought so,” he said.

She looked round quickly. “I never said so!”

“Written all over you,” replied Nat simply.

To her annoyance Phoebe found she was flushing. “There’s nothing in it; I mean he—he doesn’t mean anything by it.” She stopped, realizing she was making it worse.

“No, he’s the type who’d have a heart attack if ya took him at his word,” agreed Nat. “All talk and no do.”

“I think you’re right,” she agreed faintly, looking at him in some awe.

“’Course I’m right; ’e wouldn’t know what the Hell to do with a fine figure of a woman like you!”

“Mr Weintraub,” said Phoebe, trying to be firm but horribly aware that her voice seemed to have developed a wobble: “I don’t think—”

“And I don’t think you oughta call me Mr Weintraub,” said Nat quickly. He put his hand gently on her upper-arm; she jumped, and a thrill ran through him. “Nat,” he said, and squeezed the arm.

Phoebe turned and looked him in the eye. “Not at School,” she said firmly. “You’re a Parent.”

“Eh? Aw! See whatcha mean!” He chuckled. “All right, then; whaddabout out of school? Eh?” he squeezed the arm again.

“All right,” said Phoebe hoarsely. She swallowed. “I’d like that.”

With interest and some surprize she saw the wave of colour flood up his face. So he wasn’t as self-confident as he appeared? No, he wasn’t, for he said shakily: “God, wouldja really? So would I!”

“I could meet you this evening,” she said simply.

“Where?” said Nat.

He was breathing very fast; in spite of her own excitement Phoebe felt an unexpected wave of tenderness. “Perhaps in town; would that suit you?” Nat nodded dumbly. “What about The Royal?” she suggested. “I always like that little downstairs bar with all the fake horse brasses, and the dark panelling.”

“The Jockeys’ Bar,” said Nat. “Whaddaya mean, ‘always’?” he added suspiciously.

“I’m not a nun, you know,” replied Phoebe calmly.

Nat swallowed noisily. “Jesus, no,” he agreed faintly.

Phoebe’s mouth twitched in amusement.

“How many blokes have you got?” he said hoarsely before he could stop himself.

She laughed suddenly. “Well, there is one, at the moment, but he lives down in Dunedin, so I don’t see much of—”

Nat covered her mouth with his.

“God, I’ve been wanting to do that for years,” he said eventually.

Phoebe pushed at his chest. “Not in the office,” she said shakily.

“No—sorry.” He gave a little sheepish laugh. “Couldn’t help myself.”

“No,” she agreed softly.

Nat’s colour rose. “Phoebe—” he said, reaching for her.

“No” said Phoebe quickly, getting up. “I’ll meet you after work, okay?”

“Okay,” agreed Nat, hauling himself up. “When?”

Phoebe flushed a little. “Afternoon school finishes at three-thirty, but—”

“Good; four o’clock, then?”

“Can you get away that early?” she said weakly.

“Yeah; earlier, if ya like!” He grinned hopefully.

“No; I’ve got the littlies last thing this afternoon: human biology, so-called.” She wrinkled her nose. “Sex education.”

Nat gave a dirty laugh. “Shouldn’t be any trouble to you,” he suggested. He laid a hand gently on her bum.

Instead of pushing it away, or saying “Don’t!”, or giggling, or any of the things he would have expected, she suddenly closed her eyes, and took a deep breath. Her nostrils flared; her head tipped back.

“Christ; don’t, girl!” he croaked.

Her eyes opened as he took his hand away. “Don’t you,” she replied simply.

Nat was breathing as if he’d run the mile. “Sorry,” he said hoarsely. They stared at each other.

“I think we’d better go in to Carol,” she said finally.

“Yes,” said Nat, endeavouring to pull himself together. He looked down at himself. “Jesus, I’m stiff.”

“She won’t notice: she’s only a little girl,” she croaked.

“No, give me a few minutes.” He walked away to the window.

Phoebe stared at his broad back. “This isn’t working,” he said.

“Shall I pop down the corridor? Maybe that’ll make you feel—uh—better.”

“Worse, ya mean!” he said with a grin. “Yeah, might help; give it a go, eh?” He gave a complacent chuckle as she went out.

He waited a little but—hardly surprisingly, in a warm room that still held the smell of her—nothing happened. Finally he shrugged, and went in to Carol.

She looked very small and lost in the big chintz easy chair in the bay window. He put his hand gently on her shoulder.

“Uncle Nat!” she said, tilting her thin little face up to him in surprize. “What are you doing here?”

Nat forgot what a little pest she’d been, and all the aggro she’d caused him and Helen and her grandparents over the past few months. He bent and kissed her pale forehead. “Thought you might need me, Poppet.”

“Uncle Na-at!” wailed Carol, bursting into tears. “Why didn’t you tell me?”

“About the money?” he said cautiously, bending over her and trying to get his arm round her.

“Yuh-yes!” sobbed Carol. She didn’t try to push him away; well, that was a first, thought Nat, greatly cheered.

“Didn’t want to worry you,” he said. He knelt in front of her chair and tried to pull her against him.

Still sobbing, Carol looked up into his face. “I’d ruh-rather know!”

“Yeah; I’m sorry; only I was afraid of making things worse.” She went on crying; he got his arms right round her and said; “Come on, sweetheart, lean on me; that’s right.”

Carol put her head on his shoulder and wept unrestrainedly.

“Ssh,” he said. “There, there, Poppet; ssh; it’s all right now; ssh.”

His knees began to ache; besides which, he was still fairly stiff and one of the kid’s knees was digging into his equipment. “Come on, sweetheart,” he said. “Let’s sit down, eh?”

“What?” said Carol dopily.

Nat’s arms closed round her tightly. Grunting, he stood up slowly. “Jesus, there’s nothing to ya!” he said in horror. “You’re all skin and bone!” He sat down with her on his knee. “Don’t they feed you at this bloody school?” he grumbled.

“I’m never very hungry,” Carol replied simply. She snuffled into his shoulder.

God, poor kid! he thought. “We’d better feed you up over the Christmas holidays, then, eh?”

“Yes; I mean no. –Uncle Nat,” she said, looking earnestly into his face: “I must get a job.”

Nat kissed her forehead again. “Yeah; you can if that’s what you want, sweetheart; we’ll talk about it properly later, eh?”

“I can’t let you go on supporting me!” insisted Carol, turning scarlet.

“Why not?” He stroked a stray red-gold curl off her forehead and said: “Got nothing better to do with me dough!”

“No; don’t joke; I’m serious. You’ve got your own family to support; I’m not even your relation.”

“Whaddaya mean?” said Nat indignantly. He gave her a bear hug. “You’re me niece, aren’tcha?” He awarded her a smacking kiss, somewhere in the area of her ear.

“No,” said Carol in a muffled voice. “–You’re squashing me, Uncle Nat!”

Remembering how Melanie had adored being “squashed” when she was smaller, he went on hugging her. “Mm,” he agreed.

Carol gave a breathless giggle.

That’s better! he thought, and gently loosened his hold. “What’s all this about not being my niece?” he growled.

“We-ell ...” she began.

“You wanna be squashed again?” he threatened.

She gave a sudden giggle. “No! –But I really must get a job,” she said earnestly.

“Ssh: not now. We’ll talk it over properly later, eh? Meantime,”—he slid her gently off his lap—“I’ve come to take you out to lunch, Miss Rosen!” Grinning, he stood up.

“Really?” said Carol. She turned scarlet. “She put you up to it, didn’t she?”

“No, she didn’t, Miss Smarty-Pants; I can occasionally get a bright idea like taking me own niece out to lunch for meself, ya know!” retorted Nat.

“Oh,” she said uncertainly.

“Why don’tcha go and get out of that Goddawful school uniform and put on a pretty dress?” he suggested, leading her out into the secretary’s office with his arm around her shoulders.

“Yes, go on, Carol,” said Miss Fothergill, suddenly looking up from the papers she was reading.

“And get a move on, I’m starving!” grinned Nat.

“Oh! Yes—right!” She suddenly smiled brilliantly, and dashed out.

“Phew!” he said, grinning.

Phoebe stood up, and gave him a hard look. “You enjoyed that.”

Nat had been aware of her drifting in and out a couple of times while he’d been hugging Carol. “’Course I did,” he agreed.

The wind taken out of her sails, Miss Fothergill gaped at him.

“Only human, aren’t I?” he said plaintively. “Mind you,” he added, cupping his balls with his right hand, “I didn’t enjoy the bit where she kneed me in the balls.”

To his huge gratification Phoebe Fothergill goggled at him cupping his balls and turned puce in exactly the way his Helen did.

He jerked his head towards her office. “Come in here a mo’,” he suggested.

“No,” she said faintly.

“Just a kiss.”

“Ssh!” she hissed, dashing frantically over to the door that Carol had left open and shutting it.

Nat chuckled. “Come on, Phoebe. Ya know ya want it as much as I do.”

“Not at School,” she replied firmly. “You’ll have to wait.”

“Would one kiss hurt?” he said plaintively. He tilted his pelvis slightly towards her.

“Don’t do that!” she said sharply.

Nat laughed.

There was a timid tap at the door. Phoebe glared at him. “Go through to my office, Mr Weintraub,” she said loudly. “I’m sure Carol won’t be long.”

With a muffled snort of laughter Nat took himself into her office. He went and sat in her big leather chair behind her desk. It was pure pleasure.

“Come in!” said Phoebe crossly as the tap on the door sounded again.

“Um, I’m sorry, Miss Fothergill, but Mrs O’Connell said to ask you for the keys to the stationery cupboard...”

Phoebe gave her the keys, catching sight as she did so of the clock on Louise’s wall. “That can’t be the right time!” she said. “Kamala, have you got the right time?”

“One fourteen point two-nine,” read Kamala off her digital watch.

“Oh, no!” said Phoebe involuntarily. “Uh—thank you, Kamala; off you go.”

Kamala disappeared. Phoebe sat down heavily at Louise’s desk. She looked frantically through Louise’s address file. “Uh—yes,” she said into the phone. “Is Sir John there, please? It’s Phoebe Fothergill.”

Nat came and leaned in the doorway of her office and looked at her sardonically.

“I know; it was with me,” she said into the phone. “What? Oh; thank you.” She wrote something down. “Yes; thank you; goodbye.”

“Late for your date?” he said, grinning.

“Ssh!” She dialled frantically. “Yes—hullo? Is that The Golden Lamb?”—Nat whistled, raising his eyebrows. Phoebe tried to ignore him.—“I wonder if Sir John Westby is in the restaurant?” she said. “Could you get a message to him? Oh, thank you.” She swallowed.—Nat grinned.—“Uh—could you give him Miss Fothergill’s apologies, and tell him she’ll be there in—uh—fifteen minutes.”—Nat murmured: “Fifteen? The roads are chocker.”—“Yes, Fother-gill,” she said slowly and clearly. “Yes, that’s right; thank you so much.” She rang off and glared at Nat.

“Business lunch, eh?” he said slyly. “At The Golden Lamb? Come off it!” He laughed coarsely.

“Don’t be silly!” said Phoebe, scrambling up. “I must go—I’ll never make it—oh!”

Nat had come up swiftly as she dashed round the corner of Louise’s desk and she’d walked right into him. The heavy florid features were very close and his body was touching hers from her breasts to her thighs. She lifted her face and closed her eyes.

The kiss was as overwhelming as the first one had been. He had a trick of kind of filling your mouth with his tongue... Phoebe shuddered against him.

“I’ve got to go,” she said.

“I’m pretty far gone already,” he replied. “Four o’clock,” he reminded her.

“Yes,” she agreed.

“And for Christ’s sake don’t kill yourself on the bloody roads for the sake of that smarmy tit, Westby,” he growled.

“What? Oh! No, I’ll drive carefully.”

“See ya do,” he grumbled, and released her.

“Sorry I’m late!” he said, puffing and beaming. “Got held up at work: got back so late from dropping Carol off back at school.”

Phoebe smiled up at him and his heart started to race. “That’s okay. How was she, anyway?”

He sat down on the banquette. “Shove up a bit,” he said. When she’d moved further into the corner he slid his right arm along the back of the banquette, moved up right beside her, and shoved his warm, heavy thigh hard against hers. “That’s better,” he said with a sigh. He loosened his tie and snapped his fingers at the waiter. “All right, I think. She had a good feed, at any rate, poor kid.”

“Good,” said Phoebe, smiling at him.

“Whatcha done to yourself?” he said. “Ya look different.”

“Different? Oh, well—” She touched her heavy gold earrings and gave a little laugh. “I put these on, I suppose; and I put some stuff on my face.”

“Ya look good,” he said. His fingers touched her shoulder. “This blouse is nice,” he said. “I didn’t realize it was sleeveless, when you had your jacket on, before.” His fingers slid down to her bare arm. “Lovely,” he said, squeezing it gently.

Phoebe had had time to regret her promise to meet him: he wasn’t her type, he was loud and, frankly, rather common; and he was a Parent; she must have been suffering from temporary insanity, she’d decided. Now the insanity came back in full force. She realized, rather shaken, that he could do anything he wanted with her; and, what was more, that he knew it; and that he knew she knew it, too. In fact, the first time she’d ever met him, which had been absolutely ages ago, not long after she’d started at School, the minute her eyes had met his she’d known: there’d been that unmistakeable flash of mutual recognition, mutual acknowledgement... Kindred spirits, she thought, with an odd mixture of gloom and triumph.

“Glad you like it,” she said drily.

Nat wasn’t deceived for a moment. With a juicy chuckle he squeezed the softness of her arm again, and repeated: “Lovely.” Their eyes met; with pleasure he saw her colour rise. He himself had already risen and was dying to get her hand on him; only maybe it was a bit soon, she was a lady—whatever the Hell that meant.

Turning his head he said crossly: “Oy!” and snapped his fingers.

The skinny young waiter who had been ignoring him jumped, and bustled over. “Yes, sir, what can I get you?” he bleated anxiously.

“Some service, for a start,” said Nat drily.

“Yes, sir; of course, sir!”

Phoebe watched this performance with enjoyment; she, too, found the waiters at The Jockey’s Bar insufferable. She was quite aware that it wasn’t at all the done thing to snap one’s fingers, let alone yell “Oy” at the waiters, here—in fact several people had glanced at Nat with expressions of prudish horror on their faces and quickly glanced away again. She was very glad he’d done it.

“Whadd’ll ya have, darling?” he said to her. “’Nother one of those?”—nodding at her glass.

“Hell, no,” said Phoebe with a shudder. She glanced at the waiter with dislike. “I think it was one of their ‘ladies’ specials’—you know, fill it up with soda water and ice and wave the whisky bottle at it.”

The waiter bridled, and Nat gave a delighted snort of laughter.

“No, I’ll have a double whisky—neat.” She glanced at the waiter. “‘Straight up’,” she said kindly and very clearly. “No ice, no soda, no water, no lemon.”

“Certainly, madam,” he said huffily. “And what for you, sir?’

Grinning, Nat said: “I’ll have the same as the lady—and mind they are doubles, or no tippee—see?”

“Certainly, sir,” said the waiter, skedaddling.

“Thought you said ya liked this place?” he said, grinning at her.

“It’s gone downhill,” Phoebe replied gloomily. “They used to serve the best drinks in town; a drink that was a drink, if you know what I mean.”

“Yeah; they all get sloppy after they’ve been open a while. –What was your lunch like, anyway?”

Phoebe had been watching his wide, sensuous mouth and her thoughts had wandered. “Well, Westby was pretty ghastly, but the lunch itself was excellent.”

“Usually is, at The Golden Lamb; what didja have?”

With amusement Phoebe realized that he really wanted to know. Obediently she replied: “I had the melon to start with.”

“With prosciutto?” Nat asked.

“Yes.”

He gave a little satisfied sigh, and said: “Go on.”

“Then I had the lamb cutlets—have you had them there?”—He shook his head.—“Well, they do them very nicely: not too fatty, and flavoured with rosemary; and I had julienne potatoes and fresh peas with them.”

“Sounds good; don’t like those little chippy potatoes meself, much, though; I’da had the mashed potato, it’s good there. Didja have a pudding?”

“No; I’m not terribly fond of pudding, especially in the middle of the day. I just had coffee with a Cognac.”

Nat gave a satisfied sigh. “Sounds okay. Must go there again soon,” he decided. “You fancy coming with me?”

“That’d be nice,” she said sedately.

He squeezed her arm. “Good.”

The waiter brought them their drinks and Nat began to tell her about his lunch. Then he said cautiously: “Phoebe—”

“Mm?” She smiled into his eyes.

“Jesus, when ya smile at me like that I forget what I was gonna say...” He licked his lips. His right hand tightened on her arm. His thigh pressed against hers. Phoebe was holding her glass in her right hand. Her left lay sedately on her lap. She transferred it to his thigh.

“Jesus!” he said thickly, flushing darkly. He picked up his glass again and gulped the rest of his whisky, not looking at her.

“What were you going to say?” she said, with a little laugh.

“Eh? Oh!” he said, grinning sheepishly. “About Carol. I was wondering if I might tell her about the Macdonald business at lunchtime, since she’d taken the stuff about the money okay. Only I thought it’d be too much in one day, poor wee kid.”

“Yes,” she agreed, thinking—and not for the first time over the past few months—that loud though he might be, and certainly far from the model husband, underneath it all Nat Weintraub was a really nice man.

“Wonder if we really need to tell her at all, come to that,” he added. He rubbed his nose. “I’ll have another word with Peter about it.”

“Peter Riabouchinsky? Your brother-in-law?”

“Yeah; well, me sister-in-law’s husband, yeah.”

“I’d like to meet him,” she said. “He sounds interesting.”

Nat looked at her in horror. “No bloody way! I’m not letting you within a mile of him! You’re just his type!” He eyed her appreciatively: a big, large-boned, full-breasted woman; light brown hair, not blonde like Veronica’s and Helen’s; but still— “Not within a million miles,” he said. “’E might be doing the happily married man bit now, but in ’is time... I’ve heard some tales about old Peter...” He shook his head. “No way!”

Phoebe flung back her head and laughed.

Nat watched her with pleasure. Yeah, she was very like Veronica; and although it had been a joke, really, he decided that maybe he wouldn’t break his back to introduce her to old Peter, at that. “Come on,” he said. “Drink that up; I wanna get to bed.”

Phoebe reddened. She was far from being a prude; but none of her former lovers, most of whom had been, one way or another, in the scholastic profession, had been that direct.

Nat grinned. He’d said it on purpose, to see how she’d react. “’M I shocking you?” he rumbled.

“Just a bit,” said Phoebe. Her wide mouth twitched. “I’ll have to get used to it, I suppose!” She raised her glass and looked at him mockingly over it as she drank. Under the table her fingers gently chucked his balls.

“God!” he gasped. “Steady, Tiger!”

She gave a tiny laugh, and stopped. She stood up. “Well,” she said, “are we going, or what?”

“Going?” said Nat in a grumbling voice. “I dunno about going; I’m bloody nearly coming.”

Phoebe gave a snort of laughter.

Nat stood up, grinning broadly. He saw with pleasure the way her eyes immediately went to the most interesting part of his anatomy. “I’ll show ya what that’s like a bit later,” he said softly.

Phoebe jumped. “You don’t let up, do you?” she said weakly. Nat edged out from behind the table. “Not often,” he agreed. He put his hand on her shoulder. “This way, old girl,” he said.

Phoebe allowed herself to be turned in the right direction. Nat slid his arm around her waist. They began to make their through the crowded bar to the exit. In her ear he said: “I don’t usually let up till the both of us are satisfied.”

“I’m glad to hear it,” she replied, with a quite spurious calm: her heart was racing and there seemed to be large hollow space just under her ribcage.

Nat snickered.

They were almost at the door when he gave a jerk of surprize and exclaimed: “Micky! What the Hell are you doing here?”

One of the more elegant male backs at the bar turned, and Miss Fothergill recognized with resignation another Parent. Well, at least this one was an ex-Parent, thank God for small mercies!

“Hullo, Nat,” said Micky Shapiro mildly. “I’m getting drunk; what are you doing here?”

“Aw, we’re just going,” said Nat hurriedly. He saw that Micky was staring at his companion in surprize, and said: “Uh—d’you two know each other—uh—Micky Shapiro—”

“Yes, of course,” said Phoebe, holding out her hand. “How are you, Mr Shapiro?”

“It is Miss Fothergill, isn’t it?” said Micky, shaking hands, still staring.

Phoebe remembered him as an extremely polite man, who wouldn’t normally have allowed himself to stare like that: it didn’t really show, but he must in fact be well on the way to achieving his goal for the evening. “Yes; it’s nice to see you again,” she said calmly. “How are Susan and Allyson?”

“Oh—fine, thanks. Allyson’s going to go into the business with her grandfather—old Jerry Cohen.”

“Really? I’m glad to hear it; she always had an excellent head for figures.”

“Yes,” agreed Micky. He added earnestly: “And Susan’s going to do law next year.”

“Is she? Well, that is good news!”

“Yes,” said Micky, without any marked evidence of satisfaction.

Nat looked at him nervously. “Well, we’d better be going. See ya, Micky.”

“Yeah; see ya, Nat. ’Bye,” he added to Phoebe.

“Goodbye, Mr Shapiro,” she replied, smiling politely.

“Shit,” said Nat as they pushed their way out of the door, “what the Hell can be up with him?”

“He—er—certainly seemed to be achieving his aim.”

“Eh? Oh, getting pissed, ya mean; yeah, never seen ’im like that before—well, not for years, anyway,” he added honestly. “Wonder what the Hell’s eating him?”

“It can’t be the girls.”

“No; he might not’ve exactly sounded it, just now, but last time I spoke to ’im ’e was over the moon about young Allyson coming into the business; and when Susan decided to do law he was practically incoherent, he was so pleased... Oh, well, poor old Micky, s’pose he has his troubles... Probably a woman, now I come to think of it; yeah, he was mixed up with a proper little bitch a while back.”

Phoebe murmured agreement with this opinion and allowed him to propel her into the lift. Once they were in the lift she allowed him to put his finger on the “Close Door” button and kiss her passionately, only pushing him away when he went a bit too far and tried to put another finger somewhere else.

“No,” she said, smiling at him. “Let’s go home and do it properly.”

“Christ,” he said thickly. “Lead the way, old girl!”

Phoebe reached past him and sedately pushed the button for the carpark.

Nat’s instinct, as usual where people were concerned, hadn’t failed him. Back at the crowded bar Micky said mournfully to the barman: “Bloody women. No telling who they’ll go for. Or why. ’S disgusting.”

“That right?”

“Yes. I’ll have another double brandy, thanks.”

The bartender sized him up and decided that while the bloke could carry another, he was too pissed to know what it was; so he gave him Portuguese, and charged him for Cognac.

But in this he made a mistake.

Micky tasted his brandy and said loudly: “This is muck!”

Several people turned and stared.

Micky tasted it again and said indignantly: “This is Portuguese muck!”

Slowly and carefully he upended his balloon glass on the bar and placed it upside-down in the resultant flood of Portuguese brandy. Then he walked out.

“Drunk!” said the barman hastily, with a silly laugh. He began mopping up the flood, observing with rage as he did so that several men were giving their drinks peculiar looks. One joker actually said to his pal: “Does yours taste like Scotch, Mike? I could swear this is more like that Wilson’s stuff.” The two of them had only had the one drink each. They drank them, but they went straight out without ordering a second round. The barman was very glad when two girls—obviously office workers out on a spree—came in and asked for Fallen Angels. He put practically no spirit in them and charged twice the normal price. They paid up like lambs.

Micky knew he was far too drunk to drive. He got a taxi home, after a very long wait at the taxi rank during which he had time, although he didn’t feel any more sober, to realize that he was still thoroughly miserable. When he got home he had a shower, but still felt ghastly. Defiantly he had a brandy. By this time he was almost paralytic; he knew it, but his brain seemed to be functioning with deadly clarity. He got out his address book. He sat down with the phone, observing with pleasure that his fingers were as steady as a rock. He began to press buttons. Jillyan’s phone didn’t answer. Then he got a wrong number. Angela’s phone didn’t answer. A man answered Cathy’s phone. A strange girl answered Janine’s phone and said she’d gone to Christchurch ages ago. Barb’s phone didn’t answer. Sheila’s was answered immediately but it was one of the other girls: she said that Sheila was on the Los Angeles run at the moment and was having a layover there, but— There was a meaningful pause. Micky knew it was his cue.

“Tell her I rang,” he said dully, and rang off without giving her his name.

He looked at the book. “It doesn’t work!” he said loudly. Turning to the front of the book he methodically ripped out every single page with a girlfriend’s name on it. Inevitably he ripped out several other names and addresses on the same pages, but this didn’t seem to matter at all. He gathered up all the crumpled little bits of paper carefully and went over to his trendy fireplace. It had only once had a fire in it, at Susan’s instigation, and it had smoked so dreadfully that they’d had to put it out. He lit the pages carefully with the large alabaster lighter he kept for guests who smoked and watched them burn away.

He felt as if some huge watershed in his life had been traversed; at the same time he knew that this was stupid and melodramatic. He knew, too, that realistically it didn’t make any difference: Marianne was still as out of his reach as ever. He poured himself another brandy and pulled a comfortable chair over to the picture window. He sat there for a long time, watching the sky darken and the city lights come on, not drinking the brandy, feeling oddly purged, yet still aware that even if he had made some small cosmetic operation to the surface of his life—patched over one of the bad bits, a grubby, less creditable area—fundamentally nothing had changed. He was as rudderless and astray as he had been any time these last... well, really, since the first couple of years of his failed marriage, he thought, lucid but unmoved.

Work was—not bad, perhaps, but just work; his daughters were grown up, and with their career decisions made they had never seemed so little in need of his help or advice. The future didn’t seem dark, or even exactly uninviting: it just seemed boring. Marianne was the only thing he had actually wanted, he decided unemotionally, for about the last eighteen years. It wasn’t a matter of mere sex; indeed, sex itself seemed positively undesirable at this moment: a small, unimportant tickle on the edge of the consciousness that called itself Micky Shapiro. No, it was what she represented: something clean, hopeful, new... a fresh start.

Mid-life crisis, he said sarcastically in his head; he even thought vaguely of speaking the words aloud, but was too lazy to make the effort. He thought vaguely of making some black coffee but couldn’t be bothered to do that, either.

He was very drunk.

Next chapter: