25

The Sylvie Complication

Mirry was in the shower when the phone rang. “ELSPETH!” she bellowed. “Answer the PHONE!”

The phone continued to ring. Cursing, Mirry huddled herself in a towel and, shivering, because the upstairs passage was cold in spite of the nailed-down cream carpet that Mrs Beckinsale hadn’t been able to remove, hurtled along to Hamish’s study where the extension was. She stumbled up the stairs to the little turret that housed the study, and fell on the phone, panting.

“’Lo?” she gasped.

A soft Scottish male voice replied hesitantly: “Hullo; e-er—is that Elspeth?”

“No; it’s Mirry; didja want to speak to Elspeth?” replied Mirry, shivering.

“No,” returned the voice, not sounding too sure of itself, “actually I wanted to speak to Hamish—er—Dr Macdonald.”

Mirry had now recovered sufficiently from the flurry caused by her rush down the passage and up the stairs to wonder who the Hell she was speaking to. “Hamish had to pop into work,” she replied—apologetically, since it was Saturday, and normal New Zealand residents never went to work on Saturdays. “Can I take a message?”

“E-er, well,” said the voice, sounding very disconcerted, “e-er, perhaps...” It coughed. “Are you a friend of Elspeth’s, my dear?”

He must be an old friend of Hamish’s who hadn’t caught up with Hamish’s latest living arrangements. With a chuckle in her voice Mirry replied: “No; I’m a friend of Hamish’s, actually!”

There was a little silence from the other end of the phone, during which Mirry had time to reflect crossly that there must be something wrong with the damned phone, there was an awful echo every time she spoke, so that she could hardly hear herself think. –As it were! she thought, grinning.

Suddenly the voice said rapidly: “I see. Look, my dear, this is John Mackay; I don’t know if Hamish has spoken to you about me?”

Mirry went very red. “Elspeth’s grandfather? Ooh, heck, are you ringing from Scotland?”

“Yes; it’s rather important; could you ask Hamish to ring me back as soon as he gets home, my dear?” –John Mackay didn’t know why he was addressing a perfectly strange young woman as “my dear”, except that she sounded very young and sweet, and he hadn’t quite caught her name—the more so as in Mirry’s New Zealand accent it came out rather like “Murray”.

“Yes, I will!” she gulped. “Only he might not be home for ages; he said he had a lot to do!”

“Never mind; I’ll be here; just whenever he gets home.”

Still shaken, Mirry agreed to this, and they bade each other politely goodbye. It wasn’t until she was back under the shower, warming herself up again, that it dawned on her that, since it was late afternoon here—the shower being after some strenuous gardening—it must surely be the wee small hours of the morning over there. She did complicated mental arithmetic, but however she calculated the time difference, which she wasn’t actually at all sure of, she couldn’t make it come out much different.

“Blow!” she said finally, scowling as she climbed into a clean pair of jeans. She pulled on her violet tee-shirt and her bright pink fuzzy sweater.

“ELSPETH!” she bellowed, going to the head of the stairs.

“What?” said Elspeth, coming into the passage from the direction of the kitchen eating a Granny Smith.

“Didn’t you hear the phone?” said Mirry crossly. Damn! she thought in horror; I sound just like Mum!

“No, did it ring?” responded Elspeth mildly. “I was out the back.”

“Yes; it was your Grandpa John,” said Mirry in a calmer tone, beginning to descend the stairs.

“Aw-wuh,” said Elspeth on a disappointed note. “Why didn’t you call me? I could have talked to him.”

“I did,” replied Mirry with satisfaction, “but you didn’t answer.”

Elspeth took a huge bite of apple and asked through it: “Uh he hong?”

“He wouldn’t say,” replied Mirry. She came right downstairs and said: “But he said it was important and he wants Hamish to ring him back.”

Elspeth swallowed and said cheerfully: “Mebbe Grandma’s died.” She took another bite of apple.

“Yes,” said Mirry weakly, having come to that conclusion herself. “I think I’d better go up to the Institute and get him to ring back straight away.”

“Can’t you phone him?” said Elspeth in surprize.

“No; the switchboard’ll be closed,” replied Mirry, retrieving her duffel coat from the hall stand—a very modern, chromium affair, bought by Fog Beckinsale; Liz had always hated it; so she had conveniently “forgotten” to remove it.

“Oh,” said Elspeth. “Can I come, too?”

“I’m going on my bike,” warned Mirry.

Her face brightened. “Goody! I’ll ride my bike!”

Elspeth had talked her father into buying her a bike—something she would probably never have thought of if Mirry hadn’t had one. Hamish had been reduced to horrified silence by the price of new bikes—not that he was mean, but $900 for a kid’s bike! Mirry had very sensibly persuaded him to get a second-hand one: Elspeth would never know the difference. She was right: Elspeth loved the second-hand bike just as much as she would have a new one at four times the price: the main point seemed to be that it was her bike. It even momentarily ousted Puppy in her affections, and after she’d let him go for a whole day without food or water (Mirry was finishing an essay at the time or she’d have noticed) Hamish administered a sound spanking. Who was more surprized by this proceeding, Hamish, who’d done it quite instinctively, or Elspeth, to whom it had never happened before, would have been hard to say. She roared at him that he was as bad as Uncle Jake, and immured herself in her room for at least two hours. Hamish said worriedly that perhaps he shouldn’t have done it; Mirry, whose own father, mild though he was, would have done exactly the same, replied: “Huh! Serve her right, the little toad: how would you like to be starved and—and dehydrated for twenty-four hours?”—“That’s what I thought,” Hamish replied, comforted.

She hadn’t done any extended bike trips, yet. Weakly Mirry, who didn’t actually want to face Hamish alone with an urgent message to ring Scotland, replied: “All right; but you’ll have to keep up; this is important, you know—not a fun ride.”

Elspeth’s face took on a determined expression which was, most disconcertingly, very like the expression that Hamish’s face took on when he was in Mirry and trying not to come too soon. “Aye; I’ll keep up.”

She put on the parka that had once been Mirry’s and volunteered: “We won’t take Puppy: he’d only be a nuisance.”

“That’s right,” Mirry agreed feebly.

It was fortunate that the Institute’s prefab was one-storeyed, because they couldn’t attract Hamish’s attention by banging on the door: they had to go round and tap on his window.

When Mirry—slightly hampered by Elspeth’s interruptions—had given him the message he looked at his watch in startled way and said: “But... it must be the middle of the night over there!”

“That’s what I thought,” agreed Mirry. They looked at each other uncertainly.

“I expect Grandma’s died,” said Elspeth. “Can I have a drink, Dad? I’m awfully thirsty.”

“Aye; go along to the staffroom; you could make us a pot of tea if you like,” replied Hamish in a vague voice. Elspeth was very proud of her ability to make a pot of tea; she shot off.

Mirry looked at Hamish’s face, which, having long since lost the rather sunburnt dose of tan it had acquired during summer, was quite pale again, and saw that it had taken on a greenish tinge. His mouth was tight and strained. Feeling that her own face probably looked very similar, she said squeakily: “Shall I go, too?”

“What? No! Stay.” He put his arm round her shoulders. “This concerns you, too; stay.”

It was the first time he’d had ever indicated that anything which might affect his future could affect hers, too. Something inside Mirry trembled. “All right,” she said in a very small voice.

He leaned rather heavily on her and said in a grumbling voice: “I’ll have to get them to charge the call to our number, I suppose; damn! I’ve never done that here.”

Mirry knew that things he didn’t know how to do made Hamish cross; she felt quite comforted by the appearance of this familiar trait and said: “Let’s look it up in the phone book.”

“Aye; as a last resort,” Hamish agreed grimly; he’d already had several run-ins with the phone book.

When they were both sweaty and exasperated Mirry said timidly: “Maybe if you just rang the overseas operator... “

“Aye; but what’s the number for that?”

Mirry looked at the very confusing list of contents yet again. “This must be it.” She turned over the pages. “It’s only got the STD codes,” she said in a flattened voice.

Hamish ran his hand violently through his curls. “Och, the Hell wi’ it! I’ll dial direct: Marianne’ll know how to sort it out with the Institute’s accounts.”

“Yes; she’s marvellous, isn’t she?”

“Aye...” he responded vaguely, dialling. As the phone rang in faraway Edinburgh he put his arm round her again and held her tightly against his side. Suddenly Mirry realized that he needed her there for comfort and support; she felt very grown-up and maternal. She put her arm round his waist.

Hamish said: “Hullo—John? It’s Hamish,” and his grasp tightened painfully on her.

Mirry was very buoyed up by this, which was just as well, because Mrs Mackay had died, and Hamish, who had been very fond of her, was very much shaken by the news, even though it was not, of course, at all unexpected. He was even more shaken by the news that Sylvie intended to come back to New Zealand immediately.

“What? For God’s sake, John—! Can’t you talk her out of it?”

“I’ll do my best,” said John gloomily, “but she’s already booked her flight; so I thought I’d best let you know as soon as possible.”

Weakly Hamish thanked him.

“Did you get most of that?” he said in a tight voice when he’d hung up.

“Yes, I think so,” replied Mirry shakily. “She—she’s coming back, isn’t she?”

“Aye... Damn the woman!” he added suddenly.

Mirry felt a little better at this, and squeezed his waist consolingly.

Elspeth had come in in time to hear the end of the telephone conversation. “Do you mean Mummy’s coming back?” she asked hoarsely.

“Yes,” Hamish admitted, flushing.

Elspeth looked in a frightened way from him to Mirry. “Will she want to come and live with us again?”

“I don’t know,” he replied dully.

Mirry suddenly felt extremely sick. She let go of him—though he still had his arm round her. Elspeth just looked fearfully at him, not saying anything.

Suddenly Hamish said violently: “I don’t care whether she wants to or not; she’s not bluidy well going to live with us again, and that’s flat!”

“Good,” said Elspeth.

“Are you sure?” said Mirry faintly.

Hamish looked down at her as if surprized to hear a voice from somewhere in the region of his armpit. “Aye, of course I’m sure.”

“Because I could easily go back to the flat, you know,” said Mirry in a very high and rapid voice. “Basil and Gary haven’t got a new tenant yet.”

“No!” shouted Elspeth, bursting into tears

“No,” agreed Hamish, tightening his grip. He looked down at her dark head and said hoarsely: “You promised to stay with us, remember?”

“Yes,” she agreed in a whisper.

“YES!” roared Elspeth through her tears. “You promised, Mirry!”

Hamish said uncertainly: “It— I’m afraid it could get rather nasty; Sylvie can be very unpleasant when she tries...” His voice died away. He squeezed Mirry into his side and said: “I’ll understand if you feel you can’t face it, my wee pet.”

“NO!” roared Elspeth.

“Shut up, Elspeth,” said her father unfeelingly. He looked down at Mirry, and swallowed. “Mirry?”

Mirry said resolutely: “I can face it if you can.” She looked up at him suddenly.

Hamish went scarlet and embraced her fervently.

Elspeth watched them with dawning hope, forgetting to cry. When Hamish had stopped kissing Mirry she said: “Does that mean you will stay with us, Mirry?”

Mirry raised her face from Hamish’s chest. “Yes; come over here, Elspeth.” She stretched out an arm, still keeping the other round Hamish. Elspeth came over, rather uncertainly. Mirry put her arm round her and hugged her against them. After a moment Hamish got the point and put one of his arms round Elspeth, too. Elspeth hugged them both fervently.

When they were drinking their rather stewed tea—Hamish having added a slug of whisky to his and Mirry’s—the bottle, to Mirry’s entertainment, being kept in the bottom drawer of his filing cabinet which Marianne had neatly labelled “Sundries”—Elspeth suddenly said: “I won’t have to go and live with Mummy, will I?”

“Of course not,” replied Hamish in surprize.

“Danny Webber in our class, he lives with his mummy,” explained Elspeth. “His parents are divorced.”

Hamish replied: “That’s different; and for Heaven’s sake don’t say ‘Danny Webber he’.”

Elspeth got rather red and pouty and looked at Mirry.

Mirry opened her mouth to explain. Then she shut it again. She looked at Hamish with a mixture of doubt and reproach.

He went red and said defensively: “That child’s grammar deteriorates more with every minute she spends at that school.”

Mirry went red, too. She ignored what he’d just said and said in a high voice: “I think you’d better explain it all properly to her, Hamish.”

Hamish swallowed noisily. Reluctantly he said to Elspeth: “Danny wanted to live with his mother when his parents—e-er—split up.” He looked helplessly at Mirry. “That’s right, isn’t it?”

“Yes,” she agreed, not very helpfully.

Hamish ran his hand through his curls and said to his daughter: “The courts tend to take the child’s wishes into account in—e-er—in such cases, you know.”

“Oh.”

Feebly he said to Mirry: “I don’t think I’m much good at this.”

“Do you understand, Elspeth?” asked Mirry, without much hope.

To her elders’ surprize Elspeth replied: “It means I can live with you and Daddy if I want to, doesn’t it?”

Hamish cleared his throat.

“Yes,” said Mirry quickly.

“That’s what Mr White said.”

“Your teacher? Did he?” replied Mirry weakly. Hamish just gaped.

“Yes,” replied Elspeth with evident satisfaction.

“Did you ask him about it, Elspeth?” asked Hamish faintly, meaning had she told her teacher about her parents’ marital troubles, but not quite able to bring himself to put this into words.

“Yes, ’course,” replied Elspeth in mild surprize. “Can I use Pam’s typewriter?”

Unlike Marianne, Noelene, all of the library staff and Charlie Roddenberry, the amiable Pam Anderson had no rooted objection to having the margins and tabs on her typewriter upset by sticky little fingers over the weekend.

“Aye, go on, then,” he said limply.

When she’d gone he said, still limp: “I bet Mr White knows the private business of half the families on the Coast.”

“He’s a very nice man,” replied Mirry defensively.

“Mm.” Their eyes met. They laughed weakly.

As they were washing up their cups and saucers Hamish said abruptly, not looking at her: “It might be pretty ghastly, you know, darling.”

His voice had cracked on the last word. Mirry looked up at him sympathetically and said stoutly: “I know. ’Specially if she still won’t divorce you.”

“Yes. Or if she starts a custody battle.”

“Yes.” Mirry polished crockery furiously. “She won’t have a leg to stand on!” she said crossly. “I mean, she’s virtually ignored Elspeth for the last—what? Nine or ten months, at least.”

“Aye. But she’s still the child’s natural mother... I think the courts here are still fairly conservative about that, aren’t they?”

“Ye-es… I think you’ve got a pretty good case, though. And there’s no doubt about what Elspeth wants!”

“No.” Hamish let the water out and began to wipe the sink. He sighed. “Well, mebbe it won’t come to that.”

“No,” said Mirry squeakily. She cleared her throat. “No, maybe it won’t,” she said firmly.

Hamish put his arm around her. “I don’t think...”

“What?”

Very red, he said huskily: “If it wasn’t for you, I don’t think I’d have the guts to face it all... I think I’d just let her walk back into our lives and—and make our lives a misery,” he ended, not very elegantly.

Mirry turned and hugged him tightly. She said in a muffled voice into his chest: “I won’t go away. Not if you still want me.”

Hamish held her close. Mirry could hear his heart hammering under his cream Aran-knit sweater. It was a new sweater, in natural wool, and smelled quite strongly of sheep and more faintly of Hamish’s aftershave and of Hamish. Mirry felt as if she was going to burst into tears. She waited for him to say something terribly important or significant, such as would she marry him when this was all over, or he wanted her to stay with him forever.

Hamish was still very unsure of her; he hadn’t yet recovered from the impact of her rejection of him last December and, perhaps because he saw her so often at the Institute amongst her contemporaries, the age gap between them didn’t seem much less of a stumbling block than it had then. “Good,” he replied huskily.

After a while Mirry said into the sweater: “Have you finished your work?”

“No, but I think I’ll come home now,” he replied.

What with the business of sorting out who was to go in the station-waggon, and what they were going to do with the bikes—not to mention tearing Elspeth bodily off Pam’s typewriter—Mirry almost managed to lose sight of the fact that he hadn’t actually said anything very significant.

The Sylvie complication would have remained, at least for some little time, a complication of Hamish’s and Mirry’s private life, had it not been for one of those coincidences which, Veronica was beginning to realize, turned up wherever her husband went. If she’d thought it through logically, she would have discovered that this particular coincidence owed not a little to Peter’s good nature, and thus perhaps couldn’t have been said truly to be a coincidence, after all; but her fine analytical brain was very much under the influence of milk and baby, and wasn’t thinking anything much through.

Peter had agreed to look over some notes Mirry had prepared for her thesis, and had volunteered to return them to her at Hamish’s place, rather than require her to make a special trip into Puriri to the Institute or, since lectures had just finished and he was doing as much work as possible at home, traipse up to his house on the far arm of Kowhai Bay. The day he did so happened to be the day that Sylvie had chosen for her own visitation. As Veronica did not fail to point out, this was, of course, inevitable.

Sylvie’s taxi decanted her at the bottom of the steep drive up to the ugly white modern house, and she dismissed it irritably, ignoring the warning of its friendly driver, one Hirini Pringle, that she wouldn’t easily get another taxi to take her back into Puriri if the people weren’t home, lady. Hirini drove off with a shrug, aware that there was only him and Lesley Bentley on the road today and that Lesley might go off duty at any moment, her first grandchild was a week overdue.

Sylvie stood at the bottom of the drive, and glared at the house. It didn’t matter—though of course she hadn’t revealed this to Hirini—if “the people” were out: she had her keys. She did not, however, have her luggage. Although she’d ignored her father’s advice about not dashing back to New Zealand, she had actually registered his cautious: “I think Hamish may have someone, e-er... living with him;” so she’d prudently booked herself into a motel in Puriri. It could be embarrassing if she just turned up with her luggage—embarrassing, she meant, not for Hamish or the unknown someone but for herself. If she had to retire (temporarily) after the initial encounter, she had every intention of doing it gracefully, and not encumbered by a pile of suitcases.

Today’s visit, at ten in the morning, might or might not provoke a confrontation: without thinking it over at all clearly, Sylvie had chosen a time at which everyone might reasonably be expected to be out; if they were, then she had every intention of quietly reconnoitring the territory—the state of the master bedroom in particular, though she hadn’t voiced this thought clearly to herself, either. If someone was home—well, then, “Someone” was going to get a shock, thought Sylvie grimly. She took a deep breath and strode up the drive.

What on earth Sylvie imagined she was doing, not even she could have said. She’d resolutely refused to look at any communication from Hamish or his lawyers, or to speak to Hamish on the phone, but nevertheless John Mackay had thought she had seemed to calm down over the last couple of months. She had even listened to his carefully casual chat about his plans for his move to New Zealand with an appearance of acquiescence; indeed, when he’d wondered aloud whether he should take the rather faded sitting-room rug she’d snorted and said: “Huh! That old thing! No sense in taking that: it’s faded enough already, it’d never stand the sun out there. Anyway, I know a shop in Puriri where you can get really nice body carpet.” She then proceeded to tell him quite a lot about Forrest Furnishings; John had listened in a stunned silence.

But when Sylvie’s mother died, suddenly they seemed to be right back at square one. John told himself that it was shock: response to emotional trauma. He tried to tell Sylvie this but of course she resisted the notion with utter scorn. “Huh! And what makes you the Great Psychologist, all of a sudden?” Poor John tried to point out that she wasn’t acting sensibly: with Hamish trying to divorce her, not to mention her declared loathing of the man, what in God’s name did she think she was doing, rushing back to him the very day after her mother’s funeral? Sylvie, filled with the firm conviction that she was acting sensibly, in fact doing the only possible thing in the circumstances, scarcely bothered to reply.

Placid John Mackay was driven to roar at her in exasperation: “Goddammit, Sylvie! Can’t you see the man doesn’t want you?”

“Aye, but he’s still my husband, isn’t he? I suppose I do have some rights!” Sylvie returned with bitter energy.

There seemed—at least to a man with John’s logical mind—no convincing answer to this, so he didn’t reply.

Sylvie certainly no longer loved Hamish, so she wasn’t trying to regain either his affections or her conjugal rights—in fact the mere thought of that would have appalled her. For Elspeth she felt only a tepid affection, although she didn’t admit it to herself. While she sometimes wished bitterly that she and Elspeth could go back to the way it had always been in Scotland, she experienced no real desire to gain the affections of the new Elspeth. The child seemed scarcely to have a thing in common with her any more—but this, of course, was all his fault—well, part of it was New Zealand’s fault, but that was Hamish’s fault anyway, for going there in the first place. Brooding, she’d decided that Hamish had deliberately taken over with Elspeth the minute they got to New Zealand. She was very far from admitting that her own inactivity had had anything to do with it.

But of course it had done. And, really, this had started before they reached New Zealand: it had been Daddy who before an astounded Elspeth’s eyes had known the right things to do at huge airports and on enormous aeroplanes and in hotels and at Disneyland; Daddy who had taken her to the cinema and fed her on junk food and bought presents for her, what time Mummy ignored her. Subsequent events had reinforced the picture.

That Sylvie had been completely unable to help her limp inactivity had occurred to no-one, then: certainly not to Hamish, cross, harried, worried about his new professional responsibilities and suddenly, with Mirry so tantalisingly close yet unreachable, undergoing the agonies of frustrated lust; and certainly not to brisk, efficient Jake Carrano, who had never experienced anything remotely like Sylvie’s attack of depression in all his busy life and who had been, typically of those of his temperament, quite convinced she could snap out of it if she tried. Even kind-hearted Polly hadn’t fully understood at the time—though, with young twins, there was perhaps some excuse for her. Possibly it was due to her efforts and those of Margaret, Jill and Gretchen that Sylvie hadn’t sunk right into depression that year but had actually managed to pull herself some way out of her pit; only by then it had been rather too late to re-establish the old relationship with a growing and changing Elspeth. Hamish had been there when Elspeth needed him; he had sympathized with her needs to the best of his ability and done his best to satisfy them. Small wonder that he should have supplanted Sylvie as mainstay and provider in the rather primitive mind of a ten-year-old.

He hadn’t done it on purpose; though Sylvie was convinced he had, and had said as much in a long diatribe to John Mackay when she first heard about the installation of Puppy in the household. John had made ineffectual soothing noises. Sylvie ignored these, and finished angrily: “And anyway, what’s he done that’s so marvellous? Nothing! Nothing that I couldn’t have done,”

“Aye; why didn’t you?” he replied incautiously.

“Because he never gave me a chance!” shouted Sylvie, rushing out of the room.

John Mackay, in spite of his intelligence, didn’t bother to examine the further implications of his own question; perhaps if he had, and had managed to get Sylvie the right sort of help, she might not now have been standing, scowling and panting, on Hamish’s doorstep at ten o’clock of a Thursday morning. On the other hand, since Sylvie had never been one to let herself be helped, perhaps it wouldn’t have made any difference.

Sylvie panted, getting her breath back before she rang the bell. Determinedly she ignored the sickness in her stomach. Her heart pounded but that, of course, was only the exertion of clambering up the drive. She must get back to some serious golf; she had played a fair bit in Edinburgh, but— Crossly she realized she was putting off ringing the bell. She lifted her hand in its neat pigskin glove and rang the bell.

When a little, dark-haired figure opened the door she gaped at it for an instant, not taking in that the expression on its face was one of horror rather than mere surprize.

“What the Hell are you doing here?” she demanded aggressively.

“I live here now,” replied Mirry weakly.

Sylvie gave a terrific snort. “Huh! Got you in as housekeeper, has he? Might have known he’d be incapable of lifting a finger for himself!” She brushed past Mirry and went inside.

Mirry began to say, very squeakily: “It isn’t like that,” but was forestalled by Sylvie’s loud: “Where in God’s name is all the furniture?” as she gazed in horror at the empty family room.

“The lady took it,” she said weakly, unconsciously falling back on Elspeth’s phrase.

Not surprisingly, this reinforced Sylvie’s mental image of Hamish’s and Polly’s relation as merely a little girl: Mirry’s lack of make-up, the pigtail that today hung down her back like a schoolgirl’s, and the clothes she was wearing—her pink fuzzy sweater over luminous emerald-green tights—didn’t do anything to suggest to Sylvie, who had fixed, not to say reactionary, ideas about the appearance a woman should present to the world, that her husband’s live-in housekeeper might be a candidate for his bed.

“What lady?” she demanded suspiciously.

“Mrs Beckinsale; when she sold Hamish the house she took the furniture,” explained Mirry, now very red.

Sylvie, self-centred as ever, didn’t notice the redness, but merely snorted. “Well, I suppose I’d better see what the Hell he’s been up to,” she added grimly. She marched out to the kitchen. It was full of the steam of boiling beans. “What on earth are you making here, girl?”

Mirry replied on a weak note: “I’m boiling beans; I’m going to make Boston Baked Beans; Hamish likes them. Sylvie—”

“Got you fairly chained to the kitchen sink, has he? Huh! Typical! Well, I hope he’s leaving you some time for your studies!” She gave Mirry a beady look which was very like the looks she was accustomed to get from Kay Field.

In immense discomfort she replied: “Yes. Sylvie—” But Sylvie had shot out again.

Mirry hurried after her. Sylvie made a bee-line for the staircase. Oh, God! Mirry thought. Knees going weak, she climbed in Sylvie’s wake.

Sylvie went first, rather to Mirry’s surprize, to the little room that had formerly been Hamish’s. It was apparently empty, except for the stripped bedstead. Had she looked in the wardrobe, which rather fortunately she didn’t, she would have discovered two suitcases containing clothes of her own, and her golf clubs.

“Where the Hell’s he sleeping?” she demanded.

Mirry replied in a shaking voice: “In the master bedroom.” –Wanting to add “We both are,” but her courage failing her.

“I might have known!” said Sylvie, apparently with grim satisfaction.

She went down the little crooked flight of stairs and continued along the passage to Elspeth’s turret. Her bedroom now sported brand-new red bunks, a bright yellow chest of drawers, a bright blue dressing-table and a quantity of knotty-pine shelves which housed, in addition to Elspeth’s growing collection of books, several fuzzy stuffed animals, most of which Sylvie had never set eyes on before, and a considerable amount of assorted junk. Rather unfortunately, the room also sported a fair array of Elspeth’s discarded garments, and Puppy, relaxing on the bottom bunk.

“Spoiling her rotten—I thought as much. And what is that animal doing on the bed?”

Whether because he didn’t recognize Sylvie, or because he did, Puppy lifted a lip at this last, and growled at her.

“Puppy!” said Mirry in horror. “Stop that! Come here!”

Puppy came, looking sheepish. He pushed his wet nose into her hand. “Naughty boy,” said Mirry unconvincingly.

“Well, that’ll have to be put a stop to,” said Sylvie, giving Puppy a nasty look.

Puppy gave her a nasty look back but, aware of Mirry’s disapproval and her restraining hand on his collar, didn’t dare to growl again.

Sylvie clumped down the stairs of Elspeth’s turret and began to march back along the passage towards the master bedroom. Heart sinking, Mirry followed.

The big bed had a very pretty flowered duvet—pinks, yellows and apricots on a green ground—which Sylvie had never seen in her life before. On the duvet lay scattered an assortment of books and papers and an open lecture pad with a pen on it: Mirry’s swot, as clearly as if it had been labelled. A gaily embroidered yellow dressing-gown lay on a chair on top of but not concealing a dark green silk man’s dressing-gown which Sylvie immediately recognized as the one Hamish had wasted a very large sum of money on in New York. Since Hamish had scrupulously neat habits, the room contained no scattered garments of his; it did contain rather a lot of Mirry’s, since she considered swot was more important than tidying the bedroom, and it did contain Hamish’s slippers, parked neatly beneath a dressing-table that Sylvie had never seen before (not surprisingly, since they’d bought it at Forrest Furnishings last week). The dressing-table bore the set of silver brushes that Hamish’s parents had given him when he got his Ph.D., and a clutter of feminine paraphernalia. And, final insult, the room also contained a portable television set on top of which sat a large, drunken-looking teddy bear. The swot might not have been actually labelled, but the teddy bear was: he was wearing a tie that bore the insignia of the University of Edinburgh and pair of pale green lacy panties, and was holding an obviously home-made paper flag, on which was written in a large, careful, childish hand: “Best of luck with Exams. To Dearest Mirry from Elspeth and” and, in a man’s crabbed hand that was trying to write large and clear: “Hamish.”

Sylvie turned purple. “You’re sleeping with him! You little slut!” she cried, whirling on Mirry.

Mirry shrank, but replied valiantly: “I love him!”

In a blind fury Sylvie dashed over to the television set and hurled the offending bear across the room. He landed on the bed, squashing his flag.

“Get out of my house!” she shouted.

Mirry rushed over and picked up the bear, cradling him to her. “Leave my teddy alone!” she cried absurdly. At the same time Puppy emitted a blood-curdling growl and bared his huge teeth at Sylvie.

“Get out, you little slut, get out! And take that animal with you!” yelled Sylvie.

Madly clutching the bear, Mirry replied loudly: “I won’t! Hamish loves me—he wants me to stay!”

“Get out and take your bluidy television and your bluidy toys and your bluidy dog with you, you filthy wee whore!” howled Sylvie.

Tears starting to her eyes, Mirry cried: “I’m not! And I won’t! So there!”

Sylvie opened her mouth to reply but Puppy produced another growl, even more blood-curdling, and crouched. His hackles rose.

“Puppy! Down!” screamed Mirry.

Puppy paused. He looked doubtfully at her.

Sylvie cried, in a voice high with fear: “Get that damned animal out of here!”

Puppy crouched again.

“Puppy! HEEL!” roared Mirry. Puppy came reluctantly to heel and she put her hand on his collar and felt immensely comforted. If she says it again, she thought, I’ll let him!

Hands shaking, Sylvie picked up Mirry’s dressing-gown, together with several more intimate garments that were lying on the floor nearby, and hurled them at her. They scattered and fell nowhere near her. “And take your filthy whore’s clothes out of my bedroom!” she cried.

Mirry gripped Puppy’s collar tightly with one hand. With the other she held her teddy to her bosom, unaware that she was doing so. With considerable dignity she said: “I’m not going anywhere, I live here. Would you please go?”

“How DARE you!” gasped Sylvie. “You—you—” Words momentarily failed her. Unfortunately they didn’t fail her for long. She took a deep breath, and treated Mirry to the sort of tongue-lashing with which she used to regale her husband.

Mirry was used to Kay Field exploding at her, but that was quite different: Mum got mad with you, but it all blew over pretty quickly. The furious words floated past her unbelieving ears; they didn’t seem, really, to have anything to do with her, Mirry Field, and she stared at Sylvie’s unlovely, mottled face and, with a sort of pitying revulsion, at the spittle that gathered in the corners of Sylvie’s mouth. What Hamish had told her of Sylvie’s temper, which hadn’t been all that much, because he preferred not to talk or even think about the woman, had given her no real idea of what he’d endured. Now something he’d said about “shouting like a fishwife” came back to her, and she realized that it hadn’t been just an easy cliché, but his attempt to describe a nasty reality. Poor Hamish! she thought. Her eyes slowly filled with tears, more from pity for what Hamish must have gone through than from shock at what Sylvie was saying.

Sylvie wound up, rather incongruously, with a threat to tell Mirry’s mother all about her and her “dirty goings-on’’.

“Mum knows all about it,” said Mirry bravely. “Would you please go away!”

“Don’t you speak to me like that in my own house!” yelled Sylvie. “You’ve got no rights here, you fornicating wee slut! I’ll—”

What the next threat would have been, Mirry never knew, because she suddenly lost her own temper. “Go away this instant, you horrible woman,” she cried, “or I’ll set Puppy on you!”

Feeling the restraining hand on his collar relax, Puppy jerked forward, growling and baring his teeth.

Sylvie screamed, and shrank back. “Get him away from me!” she cried, waving her hands frantically in front of her. “Keep him off!”

Puppy lost control of himself and barked, attempting to hurl himself at her. Mirry, though still clutching Teddy with one hand, hung on to his collar with all her might with the other.

“Go away; I can’t hold him!” she panted—not altogether truthfully: Puppy was a lot stronger than she was, but he was—although young and understandably eager to take a bite of Sylvie—a well-trained dog, thanks to Jake Carrano, and wouldn’t actually have disobeyed her, however much he might have liked to.

Sweating and sick-looking, Sylvie sidled towards the door.

Puppy barked again. Surprized but happy when Mirry didn’t reproach him, he tried a growl.

Sylvie reached the door, terrified eyes fixed on his teeth, and sidled into the passage.

Puppy let himself go in a fusillade of barks.

Sylvie fled down the passage and hurtled down the stairs. The barking continued behind her; Mirry’s voice said, without any conviction at all: “Quiet, Puppy.”

At the open front door, Sylvie turned and looked up the stairs. Puppy’s barks had stopped. Defiantly she cried: “I’ll get you for this, you little whore! And if you and that damned husband of mine think you’re getting away with anything, well, let me tell you, Miss, you’ve got another think coming! You’ll see your names dragged through the courts before I’m through, never you worry!”

Abruptly Mirry appeared at the top of the stairs. She was still hugging her bear; Puppy stood beside her, growling softly.

Sylvie saw, however, that she had him by the collar, and added viciously: “Aye, and what’s more I’ll see that hound destroyed before I’m a week older; it’s a dangerous ani—”

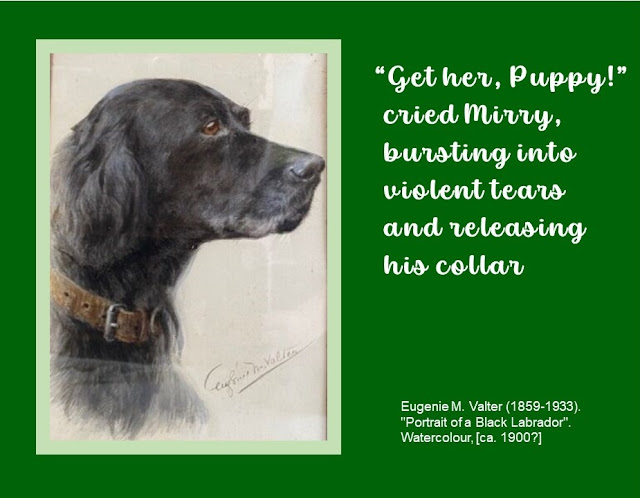

“Get her, Puppy!” cried Mirry, bursting into violent tears and releasing his collar.

The astounded Puppy gave vent to a joyous bark, before hurling himself down the stairs.

Sylvie threw herself out of the house, slamming the door in his eager black face.

Horrified by what she’d done, Mirry dashed downstairs in Puppy’s wake, tears coursing down her cheeks. She sat limply on the bottom step of the staircase as he bounced up and down, scratching at the door and barking furiously.

“Help,” she said weakly.

Puppy gave a couple more, half-hearted barks, and snuffed crossly at the bottom of the door. Then he came and sat at the foot of the stairs, looked wistfully into Mirry’s face, and whined sadly.

“Yes, the bad lady got away,” agreed Mirry. “Oh, Puppy!” She burst into a storm of sobs and hugged Puppy to her bosom, squashing the bear. Puppy licked her face consolingly.

If Peter had got there ten minutes earlier he would have witnessed this scene; he felt quite dished that he’d missed it. He turned into Kowhai Bay Road from one of the steep little side-streets—his brutal wife having declared that the walk’d do him good—in time to see Sylvie’s disappearing back—though he didn’t recognize whose back it was. When he got to the house he could quite plainly hear someone sobbing and a dog whining.

Instantly he hammered on the door, shouting: “Mirry? Are you there? It’s Peter, moy dear! Let me in!”

The door opened, the overwrought Mirry hurled herself into his arms, and the overwrought Puppy hurled himself at his legs. Peter damned nearly fell over.

Of course he got the full story out of Mirry—well, nearly the full story, he was bursting to ask her exactly who had dressed the teddy bear up like that, and under what circumstances, but with a self-restraint that was really most commendable, refrained.

“Bum!” said Veronica when he’d admitted this. She applied that fine analytical mind of hers. “I can imagine either the tie, or the panties,” she said thoughtfully, “but it’s hard to imagine both. –Not at the same time, I mean.”

“Absolutely!” agreed Peter, chuckling.

Veronica thought about it some more. “Aren’t people’s lives fascinating?” she said, in the voice of one making a brand-new discovery.

“Absolutely!” said Peter again, chuckling richly and not pointing out that the infinite yet infinitely repeated variety of his fellow humans’ lives had been the main thing that had kept him relatively sane for the past thirty years. He was beginning to have an idea that possibly Veronica already suspected it.

Veronica at that stage didn’t grasp Sylvie Macdonald’s potential for causing Hamish trouble. Peter grasped it immediately: he worried about it for some time before working up the courage to speak to him.

It hadn’t occurred to Hamish that if the Institute’s enemies in the Senate got to hear of the mess his private life had become there could be trouble. At first, as Peter had expected, he became very cold and prickly. But finally, as Peter’s sympathy and good intentions stuck out all over him, he got off his high horse.

He ran his hand through his red-gold curls and said hoarsely: “Do you really think that if the University authorities got to know about us...?” He swallowed. “I suppose, if there was some sort of formal complaint, they’d have to take notice,” he said dully.

“Da,” Peter agreed gloomily. He hesitated.

“What?” said Hamish.

Peter said reluctantly: “Well, as I h’yave explained to you, moy dear Hamish, the legal position is at best—eugh—obscure. But if it came to a court battle between us and the University”—Hamish shuddered, but he was grateful for the “us”—“I do not think that it would matter very much what the outcome was.”

“I know what you mean,” said Hamish grimly. “The damage would have been done, wouldn’t it? I’d have to resign.”

Peter replied carefully: “You would not have to resoign, moy dear fellow; and I think there would be a great deal of sympathy with your position, within the University: many people would see it, I think, as a human roights question; but on the other hand—”

“Many people wouldn’t.”

“Quoite; there is a strong traditionalist movement here, and, eugh, one of the most deeply felt traditions is that one does not, eugh...”

Before he could say tactfully “establish a relationship with a student” Hamish said grimly: “Seduce your own students; you don’t have to wrap it up in clean linen.”

Peter looked at him sympathetically and murmured: “Da,”—at the same time registering the metaphor with deep appreciation.

Hamish’s wide mouth tightened. “I take your point that I wouldn’t have to resign,” he said after a moment. “But the whole position would be untenable, wouldn’t it? The Institute’s reputation would be irreparably harmed... No; resigning would be the only possible option.” His fair skin reddened; he looked Peter in the eye and said: “The only honourable course.”

The low afternoon sun of October was coming through the window behind him and making a halo of his short red-gold curls; Peter looked with simple appreciation at the curls, the white skin with its not unbecoming flush and its few golden freckles, and, thinking idly that persons of Hamish’s complexion should never attempt to tan, replied honestly: “Yes.”

They were both silent a moment.

Hamish clasped his hands tightly together on his desk top, and looked down at them miserably. “I suppose I should resign immediately, really.”

Peter had thought that would be his reaction, so he had his answer all ready. “No,” he said firmly, “that would be most precipitate; and, indeed, quoite unnecessary at this stage.”

Hamish looked up at him doubtfully. Peter nodded firmly and said: “Da, da; I am quoite sure of it.”

“Then why bring it up at this stage?” said Hamish. His voice sounded weak and cross in his own ears; he flushed and said quickly before Peter could speak: “No—I’m sorry, Peter; of course you were right to bring it up.”

A trifle awkwardly Peter explained: “I had not intended to speak to you until after exams, believe me, moy dear Hamish; but after what Mirry told me of Sylvie’s really quoite unbalanced behaviour the other day, I thought it best that we should prepare our strategy.”

“Prepare our strategy?” he echoed weakly.

“Yes; because, just in case it has not yet dawned on you,” said Peter, with a definite twinkle, “I am very much on your soide in this, moy dear fellow.”

“Thank you,” said Hamish, going scarlet. He looked down at his hands again and said: “I’ve behaved like a damned fool, I know. I mean,” he added, looking up suddenly, “I suppose I thought that if I didn’t look too closely at the situation, it would just... that—that nothing would happen; that everything would be all right.” He stared miserably at his hands again. “Talk about a head in the sand act!” he said bitterly.

During this speech Peter had time to recollect with uncomfortable clarity just what his own part in precipitating the current situation had been, back at the beginning of May. If he hadn’t spoken to Mirry...

Quickly he said: “Yes; but you must not reproach yourself; for it is a very natural, human reaction, that; I think that most people hope that the bad thing just goes away if one does not look—da?” He held his head on one side and twinkled kindly at Hamish, what time one part of his mind sat aside and sneered at his own hypocrisy. He was used to his mind doing this sort of thing and, since it couldn’t help at this precise moment to take notice of it, didn’t.

Hamish retorted drily: “I dare say; but I bet you wouldn’t have done it, in my place.”

Peter was a little taken aback. “No-o,” he replied slowly; “perhaps maybe I would not, if I had your job; but then I am a very political animal, you know; and very much used to the sort of—eugh—back-stabbing, I think I must call it it—that is the norm at most seats of learnink!” He hesitated a moment, then added quickly: “And if you mean to imploy that I would not sleep with a student, then I must tell you that you are quoite wrong, there!”

Hamish stared at him; he twinkled ruefully and elaborated: “Oh, yes, moy dear fellow; and more than once; and certainly with absolutely no serious intentions at all—not, I think, at all loike you and Mirry?”

“No; I mean, of course I’m serious about her!” said Hamish, flushing.

“This I know,” said Peter smoothly, “for you are a very serious person, moy dear Hamish; but I—before I meet Veronica, you understand—I am not a serious person at all; on the contrary, I am a very naughty old fellow indeed, and to be surrounded, as one is at a tertiary institution, with so much lovely young flesh, is, quoite frankly, a temptation that I could not always stop moyself from yielding to. –Graduate students, moind you. And naturally it was always mutual.” He chuckled.

Hamish was goggling at him in a fascinated manner; Peter added smoothly: “I am quoite sure that Maurice Black mentions something of this to you—da?” Ignoring Hamish’s start and his Scotch noise, he gave a reminiscent sigh, and said: “I was even tempted—this was before I meet Veronica, of course—boy our own Ms Tuwhare...”

Side-tracked, Hamish said incredulously: “Darryl Tuwhare? But she’s... well, I don’t think she’s interested in men.”

“No, well, she was most certainly not interested in me! And not for want of troyink, either!” He laughed.

Hamish gave a weak laugh in reply.

Peter sighed. “I still regret it whenever I see that behind of hers in her toight black leather trousers.”

Colour flamed up to the roots of the red-gold hair, but meeting Peter’s naughty eye Hamish had to admit: “Aye, well, she’s a well-built young woman.”

“Superb,” said Peter simply. Hamish smiled; Peter continued easily: “And now, let us discuss our strategies, no?”

“Uh—yes,” Hamish replied, jerked back to more urgent matters.

Peter could see, however, that he was more relaxed after their little diversion. He didn’t wait for him to suggest anything, but immediately put forward his own idea. “It seems to me, you know, that there is nothing that can be done immediately; certainly you are roight about not upsetting Mirry during the exams; we must just let all proceed as normal—da?”

“Aye,” Hamish agreed dubiously.

Peter rubbed his nose and said thoughtfully: “Only I think, you know, it would be as well if we introduce roight from the start an official policy that at Honours level we have all the papers checked by an outside examiner—da?”

“But—” Hamish swallowed. “Aye,” he said in a strangled voice. “That—that would be ideal.”

“Not only would it help us in our present dilemma,” said Peter calmly, “it would, in any case, be a sensible policy—do you not think?”

“Yes.”

“It is quoite standard practice with theses, of course,” Peter murmured.

“Aye.”

“I know a couple of people in Wellington who would be glad to do it; also, if necessary, I am sure Veronica could suggest someone in Australia.”

Hamish sighed. “Good. Well—perhaps I should write to them? If you’d let me have their details.”

“Most certainly,” said Peter. “I leave them with Marianne—da?” Hamish murmured assent. Peter fixed him with a twinkling eye and added: “Of course, you realize that moy friends in Wellington may expect a quid pro quo.”

“Yes, of course; I’d be happy to... Whatever they want: read papers for them or—or let you do it, of course.”

“I think I should warn you that it may be a little more than that.” Hamish looked at him in a startled way and he explained placidly: “They would loike you to give some lectures to their postgraduate classes; and of course they have very little money for outsoide lecturers... A freebie, in fact!” He chuckled.

Hamish replied formally: “I should be only too glad to do that. –Presuming they still want me when the time comes,” he added sourly.

Peter said cheerfully: “Do not be so pessimistic, moy dear fellow; with a little luck we arrange all splendidly.”

“I bluidy well hope so,” said Hamish gloomily.

The fascinated Peter observed, not for the first time, that his Scottish boss combined with his flashing red-haired temper a capacity for deep gloom that he had hitherto associated more with a half-Polish friend. He repressed his interest in this matter, putting it aside to ponder on later, and said firmly: “And now: as to Mirry herself—”

The knuckles of Hamish’s clenched fists showed white; he said miserably: “I’ll have to give her up; there just isn’t any other way out of it.”

“On the contrary, there are several other ways out of it; for instance, Mirry could give up her degree.”

He watched with well-concealed amusement as Hamish looked up in a true scholar’s horror and exclaimed: “No! Good God, Peter! I couldn’t ask that of her!”

Peter was tempted to point out that Mirry might not feel so strongly on the subject; he nobly refrained, however, and merely said peaceably: “No; it could only ever be a matter of last resort, of course; I only suggest it to illustrate moy point that there are other solutions, if one looks for them.”

Hamish ran his hand through his curls again and said: “Well, what else? I can’t think of anything.”

He didn’t sound either aggressive or sulky, merely miserable, and Peter replied quickly: “Well, there is another thing I think of; but it would mean to bring another person into it; and I do not know if you would care for that...”

“What is it?” he said without much hope.

“Mirry could switch back to a history degree.”

Hamish’s mouth sagged open. After a couple of seconds he said: “But—she’ll have sat our exams... She’ll have lost a whole year.” He thought it over and said: “I can’t see them agreeing to cross-credit those papers. Her thesis... well, she’s taking a historical perspective; I suppose they might wear that...”

“Da; I am sure there will be no problem there; but as for the papers... Well, it is there that I think we maybe need a little help; we perhaps explain all to Maurice Black, and get him to intercede—da?”

“No! Good God, I can’t ask him something like that! I mean—Maurice Black!”

“But he would quoite understand, I assure you,” said Peter quickly. He leaned forward and said: “His own past is not exactly lily-whoite, you know; I could tell you things—”

“Well, don’t!” said Hamish violently. Peter looked doubtfully at him; flushing, he mumbled: “I’m sorry; but don’t you see? That makes it worse!”

“I do not see, no!” replied Peter crossly. He’d had it all worked out, and now here was Macdonald’s damned Puritan conscience getting in the way!

Hamish was silent; after a few moments Peter pulled himself together and admitted reluctantly: “I suppose I do understand, really; but don’t you think you are being... h’yow can I put it? Just a troifle over-scrupulous in the circumstances, moy dear Hamish?”

Hamish went very red and looked very annoyed. He stood up suddenly and went to the window, where he glared out across Puriri Campus at the excellent view of broad lawns and the incredibly hideous B Block, and took several deep breaths. When he felt he had his temper under control he said: “No doubt I am being over-scrupulous, as you put it. But I can’t see that two wrongs are going to make a right.”

Ah, merde! thought Peter, realizing he had put his foot into it quite deeply, there. “I did not mean in the least to imploy that,” he said quickly. “And I am quoite, quoite sure that Maurice would perfectly understand that your relationship with Mirry has been perfectly honourable from start to—”

“Honourable! She’s my student, she’s half my age, and I’m a married man, for Christ’s sake!”

“Yes, but you have not let your personal relationship influence your attitude to her on a professional level; you have always treated her just as any other student,” said Peter hurriedly. Hamish was silent. Peter said cautiously: “Besoides, she was not, when your relationship first began, one of our students at all, was she?” He was aware that this remark betrayed that he knew far more about Macdonald’s personal life than the man would probably care to have him know; but didn’t think he’d notice this at this juncture.

And, indeed, Hamish merely returned crossly: “That’s got nothing to do with it! I should never—I should never have resumed it!”

Peter sighed, and tried not to think of his own rôle in the resumption of the relationship.

Hamish glared out of the window again.

After quite some time Peter ventured: “Perhaps maybe we could at least bring up the possibility of cross-crediting M.A. papers with the History Department—their papers as well as ours, naturally. Would you perhaps loike me to broach the subject initially?”

Hamish eyed him sardonically. “Doing my dirty work for me? No, thanks; I’ll do it.”

Peter didn’t respond. For the first time in the entire session Hamish really looked at him, and became aware that he was looking genuinely distressed. His face burned; he said huskily: “My dear man; I didn’t mean— All I meant was, you’ve done more than enough already. I got myself into this damned mess, so the least I can do is—is tackle the less pleasant aspects of getting myself out of it!”

“Of course.”

The tone, Hamish thought uneasily, had been rather too formal. He hesitated, then forced himself to say lightly: “You realize that if you’d gone to the Senate with this, you could probably have had my job?”

Peter had been looking down blankly at his hands in his lap. He looked up quickly at this. Hamish smiled anxiously at him. Twinkling, he said merrily: “But I do not in the least want your job, moy dear Hamish. Perish the thought—they would expect me to publish!” They both laughed, and he added quickly: “Shall we have our afternoon tea now? It is well past three o’clock; and personally I am doyink for a cuppa!”

Hamish laughed again. “Marianne,” he said into the intercom.

“Yes, Dr Macdonald?” Marianne’s voice didn’t betray the fact that she’d heard Hamish shouting, and been horrified by it. Not that Mr Carrano hadn’t done a fair amount of shouting; but Hamish and Peter! –She didn’t address them by their titles any more in informal situations, they’d asked her not to.

“Peter needs to be revived with relays of tea,” said Hamish, with a laugh in his voice.

“Also chocolate biscuits!” said Peter into the intercom.

Thank goodness! thought Marianne. “I’ll bring the tea in straight away.”

When Hamish had had two cups of milky tea and ingested, in an absent manner, several chocolate biscuits, Peter said in a carefully casual voice: “Mirry is very broight, you know; I expect her to do very well in the exams.”

“Aye,” agreed Hamish with his mouth full. He swallowed. “Don’t worry, I won’t breathe a word of all this to her until she’s sat her papers.”

Peter smiled his nice smile and said: “I know you will not. But I was thinking...”

“Mm?” Hamish picked up another biscuit and bit into it.

Repressing a certain natural envy of the excellent white teeth and the tall, slim figure that could apparently absorb without effect as many fattening biscuits as it cared to, Peter said: “If she works hard on her thesis over the long vacation, Mirry will probably have no difficulty in finishink it next year as well as doing several history papers.” Under cover of another smile he watched for Hamish’s reaction with a certain amount of nervous anxiety.

“Aye,” he agreed shortly.

Peter relaxed. He sipped his second cup of tea slowly. After a few moments he began to chat easily about a recent exploit of Sharon’s; this led on naturally to what he’d had to pay to put a fence all along the cliff at the end of their garden; Hamish responded appropriately, if a trifle abstractedly.

However, Peter hadn’t yet finished. When Marianne had removed the afternoon tea things he stood up, but instead of making for the door, said quietly: “Hamish; I think maybe it is best if Mirry spends next Christmas holidays on her parents’ farm—no?”

“While I stay up here,” agreed Hamish grimly. “Aye; you’re quite right. I’ll make sure she goes.”

Peter hesitated. “She will understand,” he said softly, “when you explain all to her.”

“I hope so,” said Hamish, relapsing into a Celtic gloom.

Peter gave a tiny sigh, and turned for the door.

“No—wait!” said Hamish loudly.

Peter turned back.

The fair skin reddening once more, Hamish got up and held out his hand. “I can’t thank you enough,” he said awkwardly.

Peter shook hands, but he still felt a considerable amount of guilt in the matter, so he didn’t respond with his customary ease.

After Peter had gone, not neglecting to speak nicely to Marianne, she tapped on Hamish’s door, and went in. “Here are the copies of next year’s provisional lecture timetable; and John Aitken was here a little while ago; he’d like to see you, if you’ve got a moment.”

Hamish looked at her dully. “What?”

The strained, tired look on his face gave her quite a shock—in fact, it reminded her of the way Mr Carrano had looked when he’d broken up with Polly, that awful time. “Are you all right, Hamish?”

He ran his hand wearily over his face: “Aye; I’m fine... Did you say John wants to see me?”

“Yes; John Aitken,” clarified Marianne. It was very tricky, having their new lecturer called John, as well as their janitor. Poor Julia, Val’s cataloguing assistant in the library, had suggested that they call them John I and John II, like the popes, but this hadn’t been terribly well received—except by Charlie, who’d laughed loudly, and said: “Yeah; or how about John Mark One and John Mark Two?”

Hamish sighed. “What does he want, do you know?”

“He didn’t say.” Marianne hesitated. “I don’t think it’s anything terribly important; shall I make a time for him to see you tomorrow?”

Having been manipulated by Peter for most of the afternoon, Hamish suddenly revolted against being manipulated by Marianne, however tactfully and sweetly. “No; wheel him in, would you?”

Oh, well, he thought gloomily, when Marianne—giving him a last anxious look, which he pretended not to notice—had trotted off, at least it would take his mind off his troubles. He picked up the provisional timetable and looked at it blankly. After a few moments he found he was calculating how many days were left before he’d have to tell Mirry about the mess he’d got them into; and how many more days would be left after that before she had to go down to Taranaki. Then, almost three months of Christmas holidays without her stretched bleakly before him...

When John’s humble bearded face came meekly round his door Hamish’s expression was very grim indeed.

Next chapter:

https://themembersoftheinstitute.blogspot.com/2023/01/labour-weekend-part-1.html

No comments:

Post a Comment